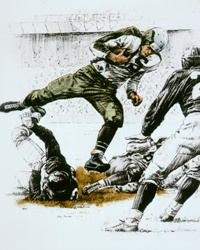

Steve Van Buren, Class of 1965

Fueled the Eagles dominating teams of the ‘40s

Steve Van Buren answered to a lot of names during his brilliant eight-year career in the National Football League – “Wham Bam”. . .“The Bayou Boy”. . .“Supersonic Steve”. . .“Blockbuster”. . .”The Flying Dutchman.”

They all could be translated to the same conclusion – even his contemporaries recognized that Van Buren, a product of Louisiana State University, would be remembered as one of the greatest football players who ever lived.

Just to make it official, Van Buren was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965. The records show that few, if any, were ever more deserving of pro football’s highest honor.

Like so many who are eventually flushed with great success, the story of Steve’s early years is not a particularly happy one. Born in 1920 in LaCeiba, Honduras, where his father was a fruit inspector, Van Buren, when he was very young, was orphaned and sent to New Orleans to live with his grandparents.

Like so many who are eventually flushed with great success, the story of Steve’s early years is not a particularly happy one. Born in 1920 in LaCeiba, Honduras, where his father was a fruit inspector, Van Buren, when he was very young, was orphaned and sent to New Orleans to live with his grandparents.

When Steve first thought of football as a sophomore at Warren Easton High School, his coach advised him to forget it because Steve weighed only 125 pounds. For the next two years, Van Buren worked in an iron foundry. When he returned to high school, he played enough football well enough to earn a scholarship to LSU.

For two years under Coach Bernie Moore, he toiled as a blocking back, and then got his chance as a running back in his junior season. In a splendid senior season, he accumulated 832 yards rushing. But, he did not win All-America acclaim and so not too many pro teams had the Tigers star on their radar. But, Philadelphia, tipped off by Coach Moore, drafted Steve No. 1 in 1944. It was to turn out to be one of the very best moves the Eagles ever made.

In spite of the fact that he was sidelined with an appendectomy for several games during his rookie season, Steve was an instant success and won All-NFL honors as a rookie. In fact, he was an all-league choice his first six straight seasons in the National Football League.

The missed games in 1944 no doubt kept Van Buren from winning the rushing crown as a rookie, but he did become the league’s leading ground-gainer in 1945 and then again for three straight seasons, 1947 to 1949. At the time that Steve was elected to the Hall of Fame, only the legendary Jim Brown had won more rushing titles than Van Buren.

There are many other marks of distinction in Van Buren’s career. He became just the second runner ever to rush for 1,000 yards in a single season and the first ever to gain 1,000 yards twice. His record of 1,146 yards in 1949 stood for nearly a decade, in spite of the increased emphasis on offense each year in the NFL during this era.

Perhaps the truest yardstick of Van Buren’s contribution to pro football can be found by studying the record of his team, the Eagles, and how well they did when he was in the fold and how they suffered when severe injuries reduced Van Buren’s effectiveness near the end of his career.

The Eagles, from the franchise’s origin in 1933, had never climbed above fourth place in the five-team Eastern Division until 1944, Van Buren’s rookie season. The Eagles just missed divisional championships in both 1944 and 1945 and then were second again in 1946.

They won consecutive divisional crowns in 1947, 1948, and 1949, and wound up winning back-to-back NFL titles in ’48 and ’49. In 1950, injuries slowed Steve and the Eagles’ fortunes dipped sharply. It would be a full decade before the Eagles earned another world championship.

Atrocious playing conditions and a rock solid defense combined to give the Eagles shutout wins in their consecutive championship game victories. In 1949, playing in the mud at the Los Angeles Coliseum, the Eagles upset the Rams, 14-0, and Steve carried 31 times for a spectacular 196 yards.

But as great as this game was for Van Buren, his best game of all time may have come a year earlier when the Eagles met the Cardinals in Philadelphia for the 1948 championship. Van Buren barely made it to the stadium as the “City of Brotherly Love,” experienced a blizzard that day. Even though more than 36,000 hardy fans managed to make their way to the game, Commissioner Bert Bell gave the players the choice of playing the game or postponing it.

The players voted to go ahead. For three quarters, the Cardinals – who had defeated Philadelphia in the championship game one year earlier – and the Eagles fought to a scoreless tie on a field where all marking were obliterated and where ordinary type of play was impossible.

Right at the end of the third quarter, Chicago fumbled on its own 17 and Philadelphia had its now-or-never chance. Four plays later, just after the final quarter had started, Van Buren burrowed over from the five-yard-line and the Eagles. That score proved to be the only one of the day and the Eagles were crowned pro football champions.

Van Buren’s personal accomplishments are many but his leadership and ability to help the Eagles reach championship status is his true legacy.

Faulk sets career receiving mark for RBs

Bears History

The Bears are one of two charter members of the NFL that still exist today.