Flores blazes trail to HOF Doorstep

By Ron Borges, Sports Illustrated

Often when a man gets a call that he’s a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame he can’t keep his eyes from watering. Tuesday Tom Flores’ eyes were welling up even before he got his call from the Hall.

That’s because the two-time Super Bowl winning coach of the Raiders had just had his eyes dilated at his optometrist’s office in Palm Springs when his phone went ballistic. Hall-of-Fame president and CEO David Baker was on the other end trying to inform the 83-year-old Flores he had just achieved his latest NFL first.

Earlier in the day he’d been selected as the first Hall-of-Fame finalist nominee from the newly established coach’s category. Considering Flores’ jewelry collection, you had to wonder what took so long.

Flores admits he’s had those thoughts a time or two himself ... but not yesterday. Yesterday his thoughts were elsewhere. Back over a career in which he has been a Hispanic trailblazer as the first Latino starting quarterback in pro football history, the first Latino head coach, the first to win a Super Bowl and the first to be named a general manager and club president.

It is often asked of a Hall nominee whether you can write the history of the NFL without him. In Flores’ case, you can’t.

“I never thought that much about it,’’ Flores once told the Talk of Fame Network when asked about the weight of history that first sat underneath his shoulder pads and later atop his signature short-sleeved silver-and-black coaching sweater. “I always figured I’d earned the right to be whatever I was. The fact of my Hispanic heritage shouldn’t have mattered. But it did matter. It mattered because of the pride certain ethnic grounds around the country felt.

“I didn’t find out until later. People I didn’t even know would come up to me and say, ‘When you won the Super Bowl my father cried.’ Complete strangers. 'My father cried.' I’ll be darned.’’

It is highly likely some fathers will cry once more in February if, as expected, Flores is confirmed by the full 48-person Hall-of-Fame board of selectors and is finally enshrined in Canton next summer, 51 years after retiring as a player and 26 years since he last coached an NFL game. If it happens, a guy known throughout his career as “The Ice Man’’ for his stony demeanor will likely melt.

“I never give up hope, but to be honest I wasn’t too excited about the possibility,’’ Flores joked when asked if he thought his time had passed. “It’s not easy to get this far. There are just so many deserving guys.’’

None more so than Flores, whose .727 playoff winning percentage (8-3) is second to only Vince Lombardi (9-1, .900) among coaches in the Super Bowl era. That puts him ahead of Hall-of-Famers Bill Walsh (.714) and Joe Gibbs (.708), as well as surefire future Hall-of-Famer Bill Belichick (.721).

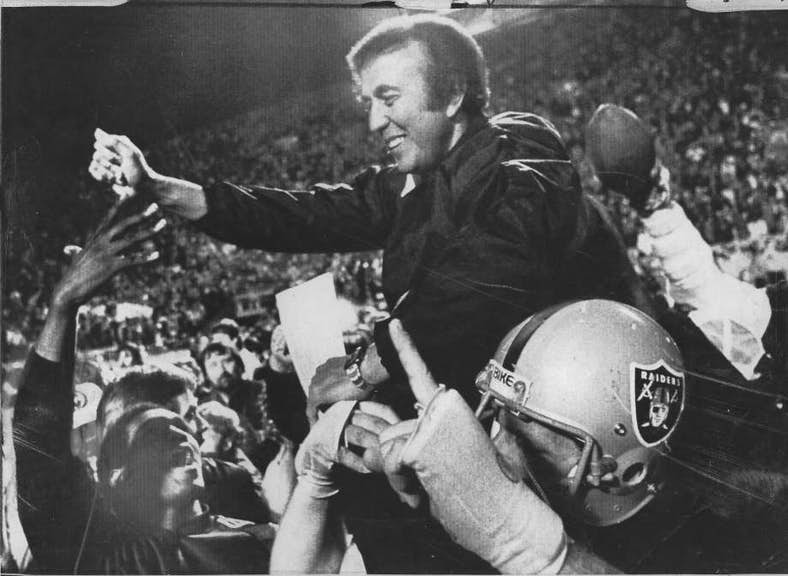

During nine seasons running the Raiders, Flores went 91-56, a winning percentage of .619, and won both his Super Bowl titles under adverse conditions. The first demanded his team become the first wildcard team to win four road games on its way to the Super Bowl XV title.

Three years later, he led the “Only On Sunday Los Angeles Raiders” to the XVIII championship. The team practiced all week in Oakland but played its games at the L.A. Coliseum while team owner Al Davis battled the league in court over his right to move the franchise to southern California.

“I won two Super Bowls in two different cities, living in a hotel for 14 months and working for Al Davis,’’ Flores once joked.

You should be in the Hall of Something after surviving all that.

Flores won those Lombardi Trophies by resurrecting the dormant career of former overall No. 1-draft pick Jim Plunkett, who came to Oakland with his confidence shot, his body bruised and his quarterbacking career in shambles after being treated like a piñata in first New England and then San Francisco.

Flores won his trust in part because they shared the same hard scrabble Latino background and thus understood each other to a depth that not normally associated with coach-player relationships.

After winning more games as the Raiders’ head coach than anyone but John Madden, Flores moved into the front office for a year before taking a job as president and general manager of the Seattle Seahawks. Once again he was breaking new ground, as he had throughout his career, but after two seasons he made the mistake of returning to the sidelines in 1992 to try and resurrect a team that had been strip-mined by then-owner Ken Behring.

Predictably, Flores had no better success than his predecessors, going 14-34 before being fired three years later. That ended his coaching career, but he would go on to serve as an analyst on Raiders' broadcasts for 21 years and work in other front office capacities.

Yet none of this might have ever happened had he not decided to throw in with a semi-pro team, the Bakersfield Spoilers, after failing to stick first with the Calgary Stampeders of the CFL and then the Washington Redskins after going undrafted in 1958. Flores was working on a master’s degree in education at his alma mater, College of the Pacific, and earning a few bucks on the side with the Spoilers, unsure whether his football days were over.

“I played because it was fun,’’ Flores said of his season as a star defensive back and quarterback for the Spoilers. “I didn’t have to practice. Just show up for the games. I got $100. That was a lot of money then. I did it for the love of the game and the 100 bucks. Probably more for the $100.’’

A year later the American Football League and the Oakland Raiders were born, and Flores’ career was reborn. He decided he had nothing to lose when the Raiders called looking for a young quarterback because he didn’t owe anyone money and didn’t have a car payment to make. He decided he’d give it one more try.

Now, 60 years later, that decision may have resulted in membership in the most exclusive club in sports – the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Along the way Flores blazed a trail for future Hispanic players and coaches and earned four Super Bowl rings, one as a backup quarterback with the Kansas City Chiefs in 1969, one in Super Bowl XI as a Raiders’ assistant coach and two when he was running the show. Not a bad ring collection for the son of immigrants who traveled from Durango, Mexico in hopes of finding a better life.

They found it, and Tom Flores lived it, even if he couldn’t quite see that when the Hall of Fame called him Tuesday afternoon.

“My eyes were so dilated I couldn’t see anything,’’ Flores said. “I just kept hearing my phone going off.’’

With good reason, as things turned out.

Shelby, NC to Immortalize Football Hall of Famer Bobby Bell. Here's How.

Already a college and Pro Football Hall of Famer, Shelby native Bobby Bell is set to receive another honor.

Tom Flores Selected as Finalist for HOF Class of 2021

Committee selects two-time Super Bowl-winning coach as nominee for election in February.