Paving the Road to Equality

5/13/2016

On November 12, 1892 the Allegheny Athletic Association (AAA) defeated the Pittsburgh Athletic Club (PAC) 4-0 in a game of football. A few weeks later, on December 27, Biddle University defeated Livingstone College by the same score.

So, other than the score – which by the way is not a typo, touchdowns in 1892 were worth four points – do these two games have in common? The answer may surprise you. Both games mark very historic events in the development of the sport of football.

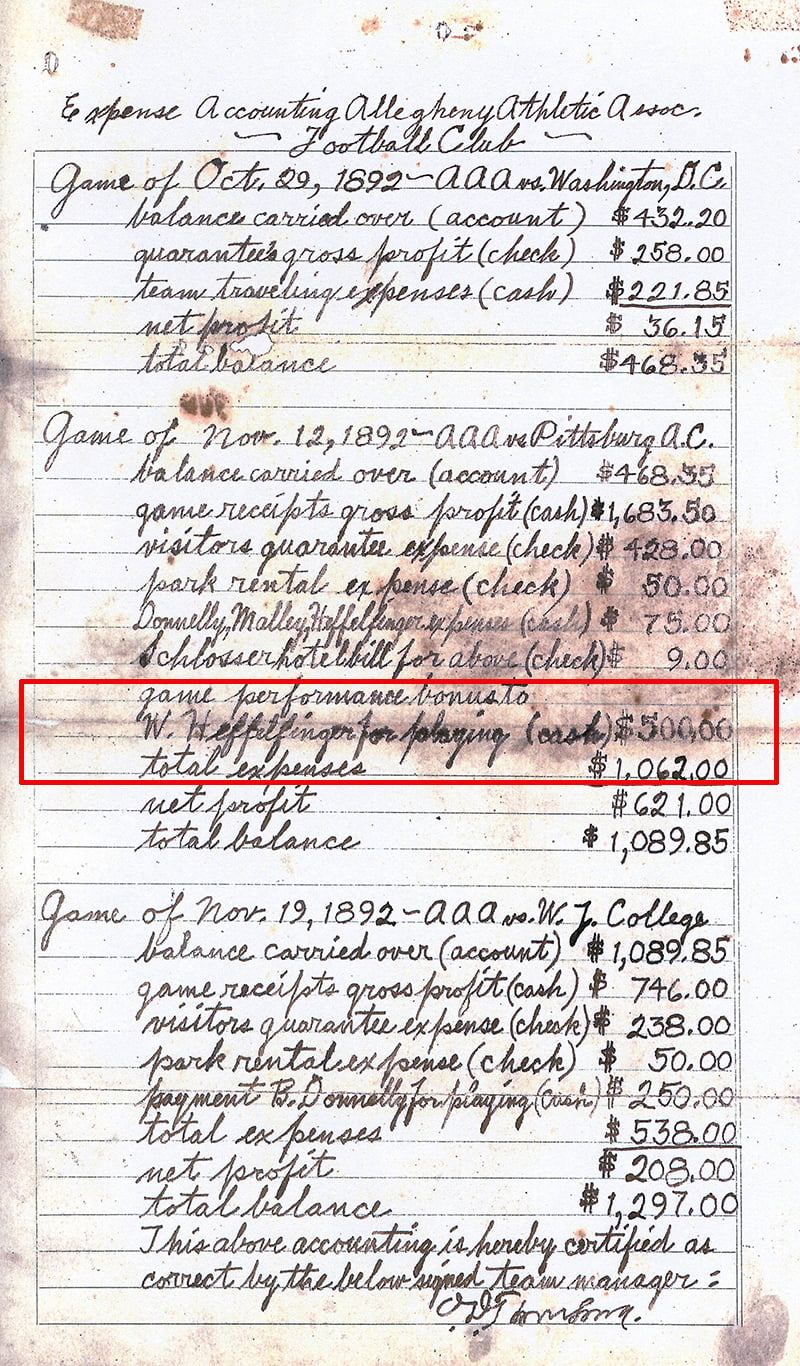

The November 12 game between the AAA and PAC was the first game in which a player was paid to play, as evidenced by the AAA’s accounting ledger sheet now a part of the Hall of Fame’s archives. The ledger clearly indicates that William “Pudge” Heffelfinger was paid $500 to play that day, thus making him football’s first professional. In other words, that was the birth of the professional game.

As for the other game, it was the first played between two black colleges. Black colleges have been around since 1837. The first, the Institute of Colored Youth, later renamed Cheyney University, was founded by a group of Quakers. As author and New York Times columnist Samuel Freedman recounts in his outstanding book Breaking the Line, “Over the succeeding decades, more than 100 other colleges and universities for black students arose in the United States, with the vast majority of those institutions springing up in the South after the Civil War.”

Some of these black colleges were indeed founded by well-meaning philanthropists or religious denominations such as the Quakers, motivated, as Freedman wrote, “with an idealistic commitment to educating and elevating a formerly enslaved people.” However, Freedman also points out, many “were created by governors and legislatures in the South as a means of preserving the iron rule of segregation and inequality in public schools.”

So now, with that historical background established, I’ll continue with my connection between the two 1892 football games. While more and more black colleges began to embrace the sport of football after that first game, so too did many small towns and cities across the Northeast and Midwest begin to welcome professional teams.

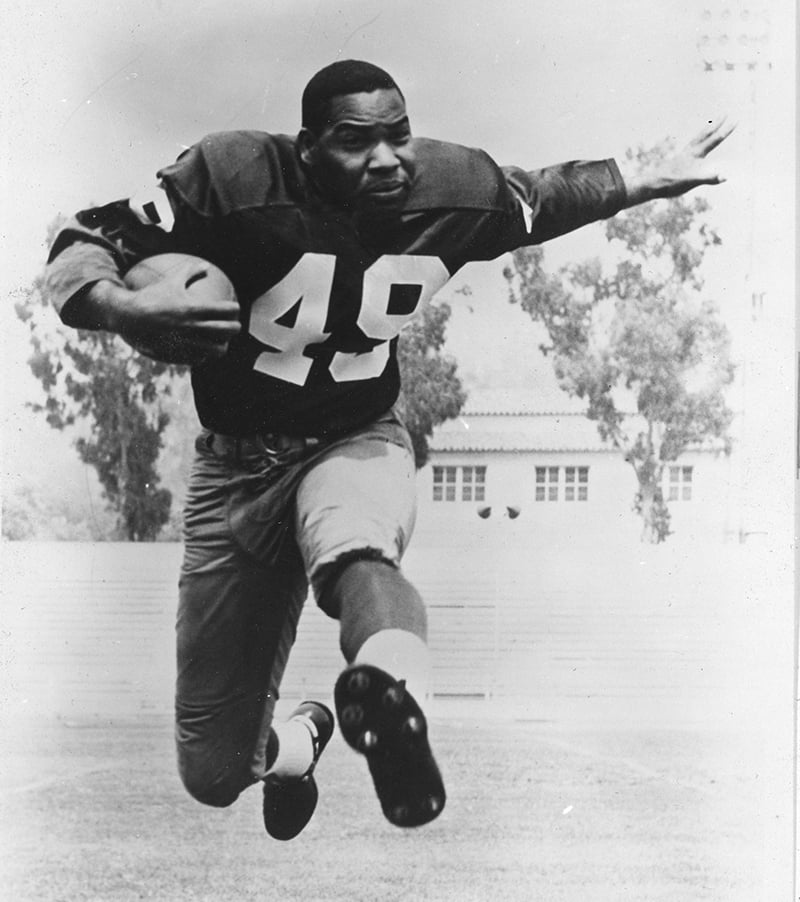

However, even as the game continued to grow in popularity and spread at both the collegiate and professional levels, it remained almost completely segregated. Between 1892 and 1920 when the National Football League was founded, only four African Americans played professionally. From 1920 until 1933 only 13. And from 1934 until 1946 there were no African Americans in the NFL.

Charles Follis (left), the first documented African American pro football player.

Historically, some pro coaches argued – or better put – defended the omission of blacks by suggesting that there were only a few playing major collegiate football for them to recruit. Well, true, there were only a handful of African Americans playing at “major” colleges, and for a good reason, most were segregated.

There was, however, as Freedman wrote, “a parallel universe of black excellence in football,” flourishing in black colleges across Border States and the South. Unfortunately, that’s pretty much were it remained for decades.

But, something happened in the 1960s that finally brought the “parallel universe” of football programs at black colleges and universities to the attention of the mainstream sports community and in the process changed the game forever. Competition.

With the start of the American Football League in 1960, there was an immediate need for quality players for the young league to compete with the established NFL. Some AFL owners, general managers and coaches realized that there was an abundance of good players who were being overlooked or uninvited to the pro game simply because of the color of their skin. Remember, it wasn’t until 1963, when Bobby Mitchell, Ron Hatcher and John Nisby were signed by the Washington Redskins, that every NFL team was integrated.

Suddenly, almost as if black players had just magically appeared on the scene, AFL rosters and eventually NFL rosters too, included players from schools like Grambling, Morgan State, Jackson State, North Carolina A&T and dozens of other black schools. A success story in the making.

Now, I think we’ve all witnessed at one time or another, that sports can serve as a vehicle that drives social change. The stories of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and their football programs are great examples of that. An entire encyclopedia of stories could and probably should be written about the social implications resulting from football programs at HBCUs. They’re not just sports stories, they’re American success stories.

And while it has been long and sometimes bumpy, the road to equality in football that began with that 4-0 game in 1892, is now paved and it leads to Canton, Ohio, thanks in large part to two African American pioneers, quarterbacks James Harris and Doug Williams. Together, in 2009, these former NFL stars founded The Black College Football Hall of Fame (BCFHOF) whose mission is to preserve the history and honor the greatest football players, coaches and contributors from Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

Interestingly, there are currently 64 Inductees in the BCFHOF. Twenty-nine are also members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, including Willie Lanier, Michael Strahan, Art Shell, Mel Blount, Jerry Rice and Walter Payton, just to mention a few. One can only wonder, though, how many more might have been in both Halls of Fame had the playing field always been level.

It is an amazing and inspiring story and one that James and Doug have worked tirelessly to preserve and share so that the lessons learned will not be lost to the ages.

So, proudly, on May, 12, 2016 football history was again made when the Pro Football Hall of Fame and the Black College Football Hall of Fame announced a partnership that will provide the BCFHOF with a permanent home in Canton, Ohio at the PFHOF. Another chapter in the story of the sport we call football will now be forever preserved for future generations to learn from, appreciate and benefit.

Welcome to Canton.

Go back to all blog listings