Mitchell integrates Redskins

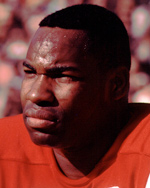

Few offensive stars ever found more ways to inflict telling damage on a National Football League opponent than did Bobby Mitchell in his 11 seasons with first the Cleveland Browns from 1958 through 1961 and then the Washington Redskins for the next seven seasons.

Few offensive stars ever found more ways to inflict telling damage on a National Football League opponent than did Bobby Mitchell in his 11 seasons with first the Cleveland Browns from 1958 through 1961 and then the Washington Redskins for the next seven seasons.

His dossier is full of astounding statistics but two stand out above all the others. During his career, he amassed 14,078 combined yards, a total only Jim Brown and O.J. Simpson had surpassed at the time of Bobby's induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Bobby also scored 91 touchdowns -- eighteen of his tallies came on rushing plays, 65 on receptions, three on punt returns and five on kickoff returns. It is little wonder that NFL defenders winced whenever Bobby got the ball.

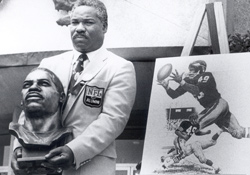

To those who played with and against him, it was never doubted that Mitchell would eventually be elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In their minds, the only question was "when". "When" came in 1983 when Bobby was elected with four other luminaries, Sid Gillman, Bobby Bell, Paul Warfield and Redskins teammate Sonny Jurgensen .

To those who played with and against him, it was never doubted that Mitchell would eventually be elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In their minds, the only question was "when". "When" came in 1983 when Bobby was elected with four other luminaries, Sid Gillman, Bobby Bell, Paul Warfield and Redskins teammate Sonny Jurgensen .

Mitchell, who was a seventh-round draft pick of the Cleveland Browns in 1958, established what would be a lasting reputation as a big-play scoring threat in his first game after signing a pro contract. In the College All-Star game, Mitchell raced behind Detroit's all-pro defensive back, Jim David, on an 84-yard bomb and then scored again on an 18-yard aerial from Jim Ninowski as the All-Stars' upset the Lions, 35-19. Mitchell and Ninowski, both of whom were drafted by the Browns, shared game MVP honors.

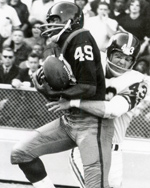

His All-Star game touchdowns were just the first of many spectacular scores Mitchell would produce in the next 11 years. As a rookie with

Bobby continued to make the big plays after joining the Redskins in 1962. In his first game in

Mitchell was born June 6, 1935, in

Mitchell was born June 6, 1935, in

Bobby had a particularly good sophomore year with the Illini. The first time he handled the football, he raced 64 yards for a touchdown against

Mitchell was even more successful in track, setting a world record (one that lasted only six days) with a 7.7 mark in the 70-yard indoor low hurdles. He ran the 100-yard dash In 9.7 and broad jumped 24 feet, 3 inches. In the Big Ten championships, he scored 13 points to pace

Mitchell was blessed with three natural talents — exceptional speed, uncanny faking ability and balance — that were to vault him into pro football stardom. Yet in spite of these obvious abilities, the 6-0, 195-pounder was not drafted until the seventh round in 195B. Somehow, the word had gotten around that Mitchell suffered from "a bad case of fumble-itis".

As the 1958 draft progressed and Bobby remained undrafted, Paul Brown , the

Mitchell felt he was too small for a pro halfback and he told the Browns' representative, Paul Bixler, that, if he signed, it would have to be with the understanding that he was to play flanker. Bixler assured Bobby that, since the resident flanker, Ray Renfro, was ailing, he would have ample opportunity to play that position.

Mitchell felt he was too small for a pro halfback and he told the Browns' representative, Paul Bixler, that, if he signed, it would have to be with the understanding that he was to play flanker. Bixler assured Bobby that, since the resident flanker, Ray Renfro, was ailing, he would have ample opportunity to play that position.

But Renfro bounced back more quickly than expected and Bobby found himself back at halfback, where Coach Paul Brown felt he would be an ideal running mate for Jim Brown. The coach did recognize Mitchell's potential skills as a pass catcher but he felt that, from a halfback spot, Bobby could utilize his ball-carrying abilities more completely.

During his tour years in

Still, Paul Brown was committed to the idea of another big back to pair with Jim Brown and he longed for a chance to acquire Ernie Davis, who like Jim Brown was a collegiate superstar from

But things were changing in

Left with no other choice,

Bill McPeak, in his first year as the

"I like to catch the ball as well as run with it," Bobby said. "Everyone said I had the best hands on the

"I like to catch the ball as well as run with it," Bobby said. "Everyone said I had the best hands on the

For two seasons, Snead and Mitchell did team up in an unusually potent pass-catch attack. Bobby led the NFL with 72 receptions for 1384 yards and 11 touchdowns in 1962 and came right back with 69 catches for 1436 yards and seven more touchdowns in 1963. The next year, Jurgensen replaced Snead as the

During this period, Mitchell won more than his share of honors. He was an All-NFL pick in both 1962 and 1964 and he earned three more Pro Bowl invitations to go along with his 1960 bid when he was with the Browns. In the 1964 Pro Bowl, he was the game's top pass catcher.

In 1967, Otto Graham, who had been Bobby's All-Star game mentor eight years earlier, opted to move Mitchell back to halfback to ease a personnel crisis created in part, at least, by Graham's decision a year earlier to move the team's best running back, Charley Taylor , to wide receiver. Bobby enjoyed only moderate success running the ball but he did catch 60 passes for 866 yards and six touchdowns.

Vince Lombardi , who came on the scene in 1969, promised Bobby a return to the flanker's job and Mitchell eagerly looked forward to a fresh start. But as training camp progressed, he realized that his 34-year-old legs had simply given out. Lombardi accepted his retirement decision and quickly installed Bobby in the Redskins' personnel department.

At the time of his retirement, Mitchell ranked in the upper echelon in most of the NFL's career statistical categories.

Many Bobby Mitchell fans contend that his Pro Football Hall of Fame election was long overdue, coming as it did in his 10th year of eligibility.

If this premise is correct, it may be that the answer lies in Bobby's extreme versatility that is clearly evident in those statistical rankings. He did exceptionally well in many offensive endeavors but did not rank No. 1 in any one department. This may have worked as a sort of smoke screen when previous selection committees judged his qualifications.

In the long run, however, it was impossible to ignore Mitchell's more valuable — and much more unusual – trait of being able to do lethal damage any time he carried the football, no matter how he gained possession.

Charles Follis led early black pioneers in pro football

The first African American professional football player was Charles Follis, who played as early as 1902.

1933 NFL Championship Game

Sweeping changes to the NFL during the 1932 offseason resulted in the league dividing into two divisions and the winners playing in a league title game.