The Trick Play Originates with a Pop

By Jon Kendle (@JKAdlibbin)

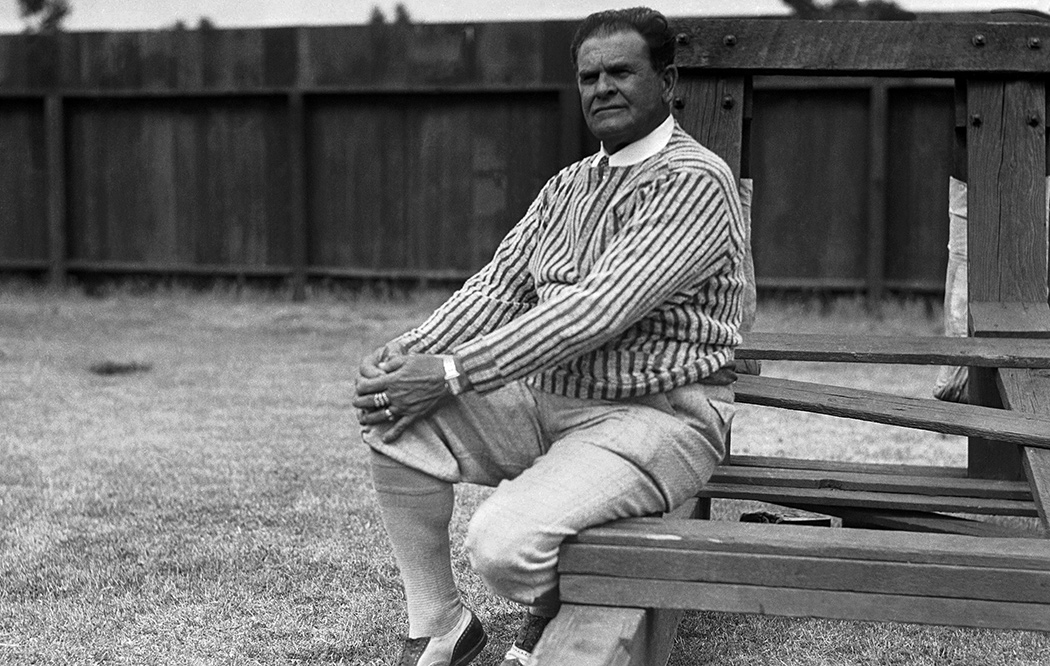

The students of The Carlisle Institute in Pennsylvania took up American football in 1895. The game, still in its infancy, was in a constant state of evolution. For the next 20 years, the Indians, under the creative tutelage of coach Glenn "Pop" Warner, wrestled their way against Ivy League teams such as Harvard, Princeton and Yale to be remembered as one of the early premier football powers in this country.

Knowing that his Carlisle teams were typically undersize and outmanned, Warner developed an innovative array of trick plays, reverses, end-arounds and flea-flickers. Warner studied the early rules and was never afraid to exploit loopholes to his advantage. For example, in 1908, he came up with a particularly brilliant trick. The rules allowed players to wear elbow pads, so Warner outfitted his team with a specialized set of pads that looked like a football when the players' arms were crossed at the chest. The pads obviously baffled defenders who could no longer tell which one of Warner's players was carrying the ball.

However, it was years earlier, in 1903, that Warner’s most creative (and controversial) trick play was developed and utilized in a game. By that time, Carlisle had developed somewhat of a rivalry with Harvard. Though the Indians had never beaten the Crimson, they always gave them a game.

Weeks before their showdown, Warner introduced the Indians to a play he had dreamed up as a young coach at Cornell. It was called the "hunchback" or "hiddenball" trick, and it was more of a stunt than a play. The play required all eleven players and a sewing machine. Warner enlisted the help of Carlisle's tailor, Mose Blumenthal, who owned the men's clothing store in town.

Warner had Blumenthal sew elastic bands into the waists of two or three players' jerseys. Among those he selected was Charles Dillon, one of Carlisle’s larger players, at nearly six feet and 190 pounds. Dillon, a perfect choice to run the play, played guard on the Carlisle line, but was very light on his feet and able to run a 10-second hundred-yard dash.

Warner wasn't sure the play was entirely legal. And the truth was, Warner was a little embarrassed to rely on tricks instead of the more conventional power game being played at the time. "Neither the Indian boys nor myself considered the hidden ball play to be strictly legitimate," he said later. But Warner believed the play would punish any team that took the Indians lightly. And there was one team that tended to do so, The Harvard Crimson.

The play was designed for a kickoff and with Carlisle leading Harvard at the half “Pop” was ready to unveil trick up his sleeve. Set to receive the ball to start the second half, Warner instructs his team to run “hiddenball.” As the ball descended into the arms of quarterback Jimmie Johnson, the other players huddle around him, facing outward. Hidden from view, Johnson slipped the ball up the back of Dillon's jersey as starting end Albert Exendine pulled out Dillon's elastic waist. The huddle split apart, and each player feigned carrying the ball. The Harvard Eleven had no idea which player possessed the ball. By the time they realized what had happened, Dillon was tumbling across the goal line.

Ultimately, Harvard’s physicality proved too much on that day and they would go on to win the game 12 to 11. However, the excitement generated not only by the trick play, but the determination and execution by the Indians against Harvard made national headlines. The New York Times called it "one of the most spectacular, unforeseen and unique expedients ever used against a member of the big four."

While celebrated, the play was controversial, and some football experts disapproved. At the University of Chicago, Head Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg termed it "parlor magic." Walter Camp, the father of American football, decided that while it was clever and technically legal, it was a bad precedent and it would ultimately be outlawed.

Black College Football Hall of Fame Class of 2019 Announced

Seven inductees were selected from a list of 25 Finalists who had been determined earlier by the BCFHOF Selection Committee.

Terrell Owens to Receive Hall of Fame Ring of Excellence During Week 9

San Francisco 49ers to pay tribute to Hall of Famer during special ceremony.