Randall McDaniel a Difference-Maker for Young People Worldwide

Story Courtesty of Minnesota Vikings

In the photograph, a young boy named Lithabile wore a grin warmer than his navy blue jacket.

He held a purple sign proudly above his head: Randall McDaniel’s Charity Golf Classic || Team Lithabile.

The photo hung on a golf cart in Victoria, Minnesota, more than 9,000 miles from where Lithabile lives at Open Arms Home for Children in Komga, South Africa. On a cart nearby, an older child, Nana, was pictured.

Thank-you cards – handwritten notes from each child expressing gratitude to Americans who would spend an afternoon golfing to raise money for Open Arms – made the overseas trip.

“You’re playing for that child, that team,” Randall explained of the photographs and cards.

Added his wife, Marianne: “He wants people to know why they’re there.”

McDaniel is no stranger to the golf course – or to charitable efforts – but this fall marked the first tournament he personally hosted. He was joined by 11 fellow Vikings Legends, from fellow Hall of Famer Paul Krause to Steve Jordan and Henry Thomas, former teammates who traveled from out of state for the occasion.

When all was said and done, the tournament raised $73,000 for Open Arms, which was founded in 2006 by Bob and Sallie Solis.

After traveling to South Africa on a family mission trip in 2005, the Solis family felt compelled to do something for children in the country who have been orphaned by AIDS.

Bob and Sallie took their life savings, bought a 70-acre hilltop farm, began raising money to buy furnishings and an old car and sought a license to take in orphaned children. On March 16, 2006, a 2-year-old boy named Sifundo was the first child to come to Open Arms.

Almost 14 years later, the home now cares for 58 young people, all of whom are also provided (if old enough) tuition and uniforms for school. Five children are also enrolled in post-secondary education.

The connection between the McDaniel and Solis families is a deep one. In fact, it dates back to a friendship between Randall’s and Sallie’s parents, who worked citrus fields together and lived in camps that did not have water or electricity.

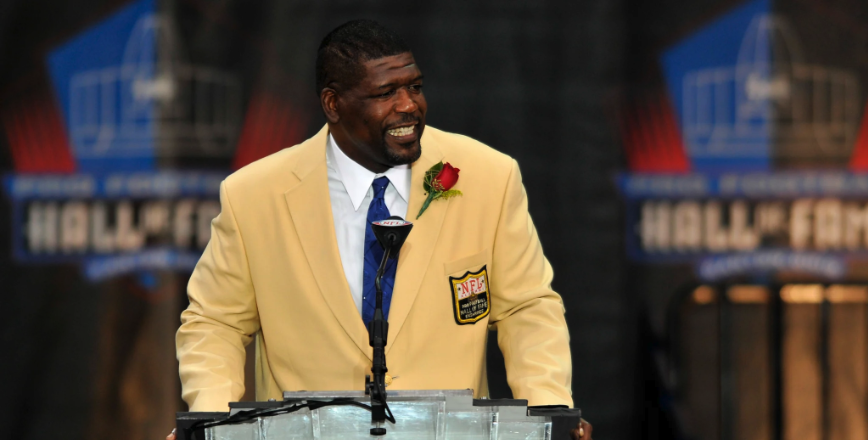

“From that bond back in the day, Sallie and I have always been friends,” said Randall, who explained that although their lives took them down different paths, they and their spouses reconnected in 2009 when Randall was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

At the time, Bob had just completed a 700-mile walk across South Africa to raise $250,000.

“He just says, ‘Someone had to do something,’ ” Randall said. “Bob is a warrior. I don’t know how he does it.”

So when the McDaniels were approached about hosting a golf tournament to help support Open Arms, they jumped at the chance to help.

Pink shorts & ‘Where the Wild Things Are’

It may be a more recent endeavor to actively support a group of youth living on another continent; impacting the lives of young people, however, is nothing new for Randall.

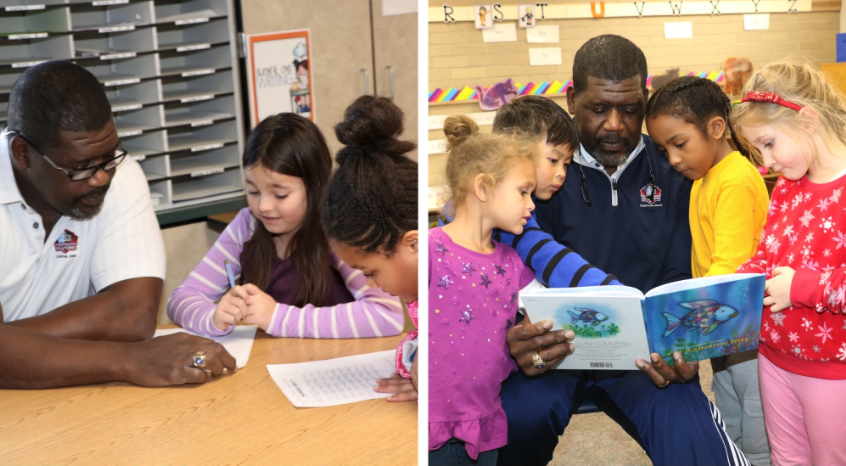

Some may be aware that Randall works full time as a basic skills instructor and tutor at a Twin Cities elementary school. What may be lesser-known, however, is the backstory behind the Hall of Fame icon who spends his days folded into miniature, colorful chairs.

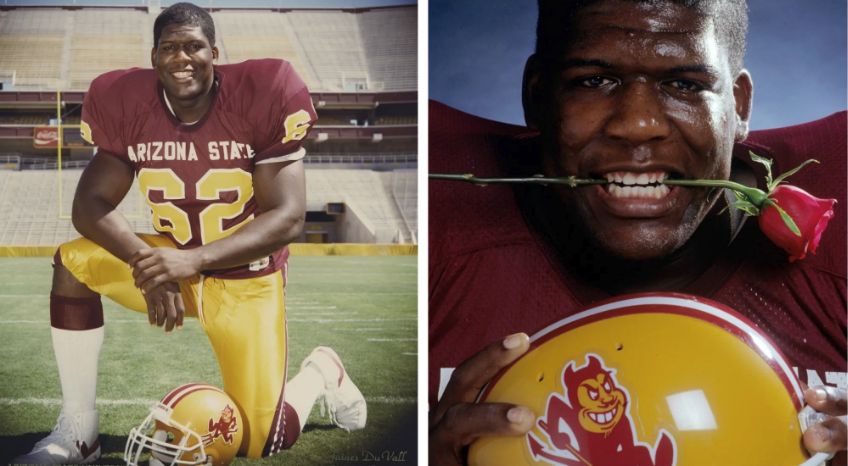

Randall attended Arizona State University, where he excelled on the football field but also dedicated himself to academics, initially as a physical education major. It was during his time at ASU and through a friend, Jody, that Randall first discovered his gift in the classroom.

An eighth-grade teacher where Randall was student-teaching, Jody one day approached him with a problem: the young men in her classroom refused to read aloud in class, citing that “only women read.” She asked Randall if he would be willing to sacrifice his lunch break, bring his favorite book and read to her class.

The next day, Randall showed up with a copy of Where the Wild Things Are.

“You could see it. The boys were looking at me like, ‘He’s reading!’ I was doing the voices and everything,” Randall laughed.

He brought a new book to read every day. And when he heard that boys in the class directed derogatory comments toward males wearing the color pink, Randall showed up in a white shirt and bright-pink shorts.

“They were staring, and I said, ‘What? Do you have a problem? I like the color,’ ” Randall said.

By the end of the semester, all of the boys wrote their own books and presented them to Randall in front of the class.

“That’s kind of when the phys-ed degree wasn’t going to be the phys-ed degree,” Randall said, smiling. “I wanted to be in the classroom.”

Just Mr. McDaniel fans

Fast-forward to 1994, seven seasons into Randall’s NFL career. He already had been named First-Team All-Pro four times and was a six-time Pro Bowler. He hadn’t missed a game in five years.

It’s fair to say that Randall had plenty on his plate as the Minnesota Vikings starting left guard, but he always found time for Twin Cities schools on Community Tuesdays.

For several seasons, he regularly spent his off days volunteering in the classroom. Not long before he left Minnesota and joined Tampa Bay as a free agent for the 2000 season, Randall met a young man, Cam Washington, who “didn’t quite fit in” with his third-grade peers.

“He was bigger than everyone, but he wasn’t playing sports at the time, and he was quiet,” Randall recalled. “Kids kind of picked on him. And he wasn’t doing well in math, so we always sat and worked together.”

The two formed a bond, and Randall “followed” him through the fourth and fifth grade, coming back to Minnesota during the offseason to fulfill his commitment to students. Randall watched Cam gain confidence and friendships as well as improve in academics.

“Randall and I had a connection,” Cam said recently. “I felt comfortable with him, and he was someone I looked up to.”

Cam one day confessed to Randall that he never had been a Vikings fan at all but rather had always rooted for the Buccaneers; so when Randall signed with Tampa Bay, Cam felt that he finally played for his true favorite team.

When asked why he had cheered for the Vikings while Randall was on the roster, Cam answered simply: “Well, I was just a Mr. McDaniel fan.”

Through the years, many Mr. McDaniel fans have come through Twin Cities elementary schools.

There was Conrad, a second-grade student with autism that Randall met in 2008.

The classroom environment and social interactions proved especially trying for the young man who spoke very little and preferred standing near his desk rather than sitting at it. While other students with sensory disorders often used a weighted vest as a calming mechanism, Conrad chose not to wear one.

Instead, he scooted his chair back between Randall’s legs, rested his arms on the tops of Randall’s thighs and leaned back against his chest.

“He’d say, ‘You’re my Big Comfy Chair.’ That’s what he called me,” Randall said. “He’d do all of his work from that position.”

Conrad’s father, David Kolb, recalled the difficulties his son faced and the frustration that accompanied. When anyone, including Randall, succeeded in communicating with and supporting Conrad, it spoke volumes.

“I was grateful and relieved that somebody was able to make some connection with him,” David said. “Whether teaching him specific skills or just putting him more at ease when he’s there – in either case, those things were valuable.”

When Conrad heard the following year that Randall would be inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, his request surprised many: he wanted to be in Canton to witness his friend’s moment.

The suggestion was both endearing and worrisome for Randall, who knew the 8-year-old could be easily over-stimulated and generally did not fare well in crowds.

But David and Conrad made the drive to Ohio. The road trip provided a sense of normalcy in their relationship – a “fun time” between father and son, recalled David – and Conrad had a solution for managing the sea of unfamiliar faces.

Randall remembered the sweet explanation:

“He had said it to me before at school: ‘Mr. McDaniel, I need to be on your shoulders so I can be above the ‘por-est.’ He had combined ‘people’ and forest’ together – the ‘people forest’ – and it’s what he called crowds,” Randall said. “I saw them before I gave my speech, Conrad on his dad’s shoulders, walking through the crowd, and they stopped at the stage. ‘I’m here now, Mr. McDaniel!’ ”

Randall smiled, remembering that moment 10 years ago.

“Above the people, he was OK,” Randall said. “He came out of his shell for me.”

More than an athlete

Randall credits specific teachers in his life for shaping him into the man he is today.

He names Mrs. Pyle, his third-grade teacher who, instead of sending him to the principal’s office when he caused trouble, worked 1-on-1 with Randall and got to know him. While he stayed after class and wrote I will not hit my classmate again 100 times, Mrs. Pyle got to the root of his academic struggles – math – and discovered his favorite treat, chocolate.

She used M&Ms to teach Randall the multiplication tables, and he learned not only numbers but also the value of being heard.

“She was the first one to really, truly get me [to believe], ‘OK, I can do the work,’ ” Randall said. “She figured out my story.”

But O.K. Fulton, a former coach at Agua Fria High School, arguably has had the biggest impact on Randall’s life.

At the 2009 Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremony, he was presented not by a family member or an NFL teammate but by Fulton. An emotional Randall said the following during his acceptance speech:

Outside of my family, he’s been the person who made the biggest impact on my life as a young man. He believed in me before I believed in myself. … Mr. Fulton, your passion to make a difference in the lives of your students, and your belief in the potential of every young person, is something I try to emulate in my second career as an educator.

Years ago, Fulton told Randall as an eighth-grader that he planned to keep an eye on him, that he wanted to “get to know the young man, not the athlete,” and he followed through on that promise.

Randall was talented enough to make the varsity football team the next year as a ninth grader, which didn’t sit well with a few of the older players. When he was jumped by a group of seniors for taking someone’s spot, the “bully side” that had become all too familiar to Randall resurfaced, and he went “house to house” serving payback.

But who showed up at the final house to stop the fight? Mr. Fulton.

“He sat there in a park on my side of town, where he shouldn’t have been, and he never left,” Randall said, admiration in his voice four decades later. “He told me, ‘You can be more than this. Sports can take you somewhere to get you out of Avondale. You can get a degree. You can do more for your parents, and sports can be the thing that takes you there. But you’re more than just an athlete.’ ”

For the first time, Randall learned to walk away from physical confrontations rather than fighting back.

“ ‘Just walk away. Tell them they owe Mr. Fulton when you walk away…’ ” Randall’s voice trailed off. “When I finally got those scholarship offers, it was Mr. Fulton saying, ‘This is what I was talking about, Big Man.’ He still calls me ‘Big Man’ to this day.

“Mr. Fulton was that difference-maker for me,” he added.

The ripple effect

It’s why Randall has dedicated years to education – before, during and after his NFL career.

It’s why he held his retirement press conference at Lakeville Elementary School in February of 2002 and later that same afternoon stepped in as a substitute teacher.

Not often do you see a Pro Football Hall of Famer walking the halls of a primary school, helping kindergarten students read and monitoring recess. Randall didn’t have to teach. He could be, as Conrad’s father said, “on a beach somewhere,” but he chooses instead to invest every day.

Asked why, he simply shrugged his shoulders and smiled.

“That’s what linemen do,” he joked.

“I think it’s what you’re supposed to do. I mean, we’ve been afforded these opportunities because of the game … what are you going to do with it?” He added in a more serious tone. “I mean, yeah, you can ride off into the sunset, retire and never have to worry about it. Or, do you try to make a difference? I’ve always felt like you’ve got to give back.”

Randall has been asked to consider working with older students, but he always declines.

“There’s not a lot of male role models in the elementary schools, and I look like a lot of the kids where I’m at,” he said, tapping his chest with his index finger. “You don’t often see a face of color, and if you do, it’s later in middle school or high school. To make that impression early is why I like elementary.”

Before starting his day as a basic skills instructor, Randall stands at the school’s entrance each morning and greets every student. He smiles, doles out high-fives and, if a student seems to be having a difficult time, he’ll pull him or her aside just to check in.

“He has this wicked ability to just tell when a kid isn’t right,” Marianne said. “It’s like this sixth sense.”

“It’s like breaking down a football play,” Randall explained. “If they walk in and there’s something not right with the read that I’m getting, then I’m automatically [having my radar up]. And I’ll keep an eye on them.”

Randall has continued to pay forward the gift he received from Mr. Fulton, and the ripple effect is widespread.

Coco Rodgers first met Randall as a second-grader at Lakeville Elementary. She remembers him helping with reading in her classroom, and she later joined her friends and participated in Team McDaniel, a volunteer program established by Randall and Marianne.

Nearly 20 years later, Rodgers works as an education assistant at, you guessed it, the same school where Randall currently works.

“It’s come full-circle. He was a positive role model for me growing up,” Rodgers said. “And the kids now love him. They want to be around him. He has that goofy, funny relationship with the kids … and he really cares about them.

“They look at him and think, ‘I want to go play basketball; I want to go play football.’ And he’ll joke, ‘Yeah, but where does it start? You have to go to school,’ and he’ll bring it back to education,” she continued. “He’s very witty with the kids, and he tells them kind of how it is. There’s an aspect of tough love.”

Cam Washington, the Buccaneers-loving third grader that Randall took under his wing, coincidentally benefited from Alan Page, another Viking in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Washington went on to excel in school and attended the University of Minnesota-Duluth with the support from a Page Education Foundation Scholarship.

The scholarship program created by Page and his late wife, Diane, requires students to commit a certain number of volunteer hours per week, and Washington opted to tutor in a fourth-grade classroom. Even beyond that scholarship year, he continued to volunteer in different Duluth-area schools.

As he approached his senior year at UMD, Washington sent Randall an email.

“As I started to volunteer more, I definitely saw [the impact],” Washington said. “I made connections with some kids, and I just loved helping them succeed in school.

“I also saw how cool of a full circle that was, that as I was growing up and going through school, giving back my time as well, similar to what Randall was doing,” he added. “I’m very appreciative to him for how he taught me that it’s good to give back when you can.”

From the North Metro to South Africa

That philosophy now has carried far beyond the Twin Cities to South Africa, where Randall and Marianne are committed to supporting Open Arms and the Solis family through the golf tournament, which will return in 2020.

“Because Open Arms has no U.S.-based staff or promotional budget – we are all volunteers – it is important to share our story with people who are in a position to help,” Bob said. “We feel that Randall and Marianne’s commitment to this cause, and our ability to share the story, will benefit our children for years to come.”

Randall and Marianne hope to one day soon make the trip overseas to meet Lithabile, Nana and the other children. He smiles as he imagines it, anticipating that they’ll “kick his butt” on the soccer fields.

Because thanks to Mrs. Pyle, Mr. Fulton and other difference-makers along the way, Randall’s passion for youth knows no bounds.

“It was an easy transition [from working in schools] to ‘I’m going to help with Open Arms.’ I mean, they’re kids,” he said. “I don’t care where you’re from, what country you’re in – kids are all the same anywhere you go.

“If I can help out in any way, then that’s what we’re going to do,” Randall added.

Class of 2020 Modern-Era Semifinalists Revealed

List trimmed from 122 nominees; Includes seven first-time semifinalists

NFL's All-Time Team: Running backs and coaches

How do you choose between Red Grange and Barry Sanders? Or Dutch Clark and Marshall Faulk?