Gotta Hand it to ‘Em!

4/2/2017

There is no doubt about it; professional football is a physical game. Injuries happen, fractures, stitches, bumps and bruises by the hundreds. Some players can tough it out and produce through the pain. Other times, the production level drops and the injured player is relegated to the sidelines to watch.

Throughout the 1960s, two professional football leagues (the American Football League and the National Football League) were rivals competing against one another for players and fans. The two leagues ultimately merged in 1970, but in the back-to-back seasons of 1965 and 1966 each league showcased the toughness of its star players. The NFL’s Larry Wilson and the AFL’s Lance Alworth, both members of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, accomplished amazing production with two broken hands (well...sort of). It’s these types of performances that elevate a player’s status from great to legendary and turn his story into folklore.

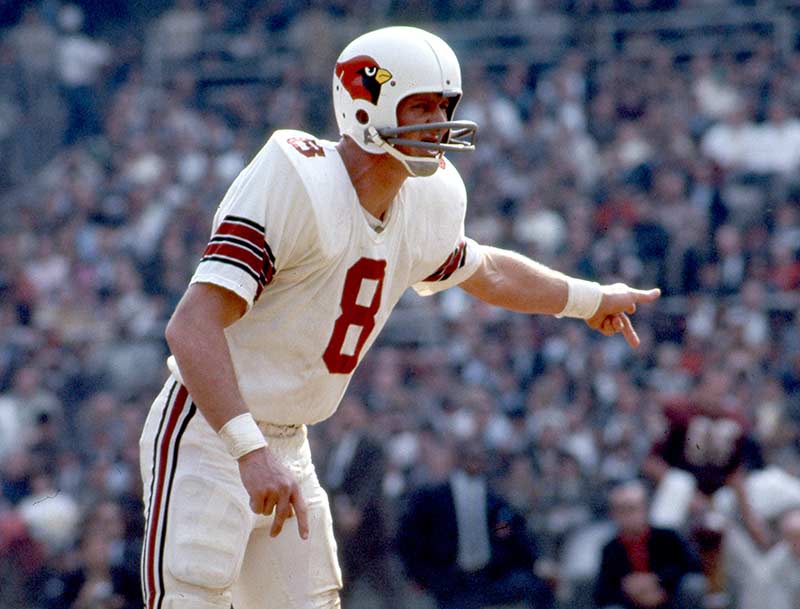

Wilson, a safety, who perfected the safety blitz and terrorized opposing quarterbacks by driving them into the ground. The legend of his toughness grew in 1965, when he took the field for the St. Louis Cardinals during a midseason match-up against the Pittsburgh Steelers. Wilson was injured a week earlier in a rough game against the New York Giants. His first injury occurred early in the game when he came up from his secondary spot to make a tackle. In the collision, he landed on his right hand. Wilson explained, “I landed on the finger. For a split second, all my weight was on it. And I knew something wasn’t right.” At halftime, he taped it up and continued to play. During the second half, Wilson once again barreled up to make a tackle and this time his left hand was smashed between the helmets of two players in the pileup. After the game, the team trainer came up to Larry to look at his finger. “Never mind the finger,” Wilson said, “You better look at this hand.” The X-rays showed a fracture across the back of his left hand, and another fracture of his right middle finger.

Regardless of the pain, Wilson ignored the advice of team doctors not to take the field. With both hands in casts and his fingertips barely showing, he not only started the game, but practiced the entire week leading up to it like normal. He couldn’t button his shirts or cut his food all week, but on game day the trainer put a foam rubber pad on each of his casts and Wilson went out to play. During the game, he proved that a banged-up Larry Wilson is better than most healthy players. He not only performed his duties but made a game-changing play when he tipped a pass from quarterback Bill Nelsen to himself and as he cradled the intercepted ball into his body, he returned it 35 yards which set up the go-ahead touchdown. To Wilson, pain was just a part of the game. He stated, “If you don’t get hurt, you haven’t played.”

Wilson remained in the lineup one more week and then opted for surgery on the finger of his right hand as the bone was sliding down to the palm and getting worse. Wilson sat out four games, but talked his way back into the lineup for the season finale against the Eastern Division Champion Cleveland Browns. He had healed enough to play and wore only bulky pads around each hand. The slight freedom must have helped as he intercepted three of quarterback Frank Ryan’s passes and returned one of them for a then team record 96-yard touchdown.

The next year Alworth, of the AFL’s San Diego Chargers, followed Wilson with an “I see yours and raise you one” type of season in 1966. As a receiver, Alworth made his living catching footballs. Unfortunately, two preseason injuries severely limited his ability to do that without immense pain. Whenever the media asked him how he felt in the early part of ‘66, “fine” was the simple answer he gave. Most people didn’t know Alworth was hurting. Even fewer people knew what he was battling.

The fleet-footed receiver had chipped a bone in his right hand against the Oakland Raiders during Week Four of the preseason. The very next week against the Kansas City Chiefs, although he only played sparingly, his quarterback John Hadl left a ball short on a “go” route and as Alworth jumped to grab the ball out of the air he ran into the defender and fell on his left wrist. X-rays after the game revealed a fracture.

Most receivers would have packed it in at that point. Opting for a cast on both hands and wrists and missed at least half of the season. Not Alworth, he preferred a 5-inch leather brace and some tape. As he explained, “The cast would have immobilized the hand for eight weeks. This way I play week to week, hoping it heals in place.”

Neither the Chargers nor Alworth talked about the injuries till midway through the season for fear that other teams may try to aggravate the injuries or play a different style of defense than they would usually play against San Diego’s potent passing attack. Instead Alworth kept quiet and kept producing. He compiled eight 100-yard receiving games, five games scoring multiple receiving touchdowns and an astounding 18.9 average per reception.

When the season ended, Alworth had not only earned his first AFL receiving title with 73 receptions, 1,383 yards and 13 touchdowns, but also changed the perception many people had about the 6-0, 184-pound flanker’s toughness. Fewer and fewer people referred to him as “Bambi” as they did in his younger days for the smooth and graceful way he moved in and out of breaks. Instead he earned a new nickname that coincided with his legendary toughness the “Mean Gnat.”

Go back to all blog listings