HOF 16 Most Unusual Artifacts

Heating Coil from Lambeau Field (failed in the Ice Bowl)

This coil might seem like a hunk of junk, but it played a significant role in one of the most historic games in NFL history, the 1967 NFL Championship Game, better known as the “Ice Bowl.” This coil was part of the heating system that was installed 6 inches underneath Lambeau Field from 1967-1997. But the system backfired in the “Ice Bowl.”

A tarp was placed over Lambeau Field the night before the 1967 Championship Game. As the field crew removed the tarp in the morning, they noticed quite a bit of condensation had formed on the grass, but the field was not frozen. The heating system had done its job, but had it done it too well.

The engineer who installed the system instructed the Packers to keep the system off during the game. His reasoning was if the heating system continued to run during the extreme temperatures, it would need so much power to keep the field from freezing that the system would over-heat itself and be destroyed. Once the tarp was removed, the condensation that had formed immediately froze in the 13 degrees below zero temperatures. The field literally became a sheet of ice. Because of the extreme temperatures and terrible condition of the field, the game became known as the "Ice Bowl."

Paul Brown’s Ball Warmers (failed experiment to keep footballs warm)

One could argue the father of modern football is Paul Brown. He was known for numerous coaching innovations, such as being the first to use intelligence tests, classroom techniques and film study for player development and evaluations. He was also an innovator as far as equipment. He worked with Riddell to develop the lightweight bar-tubular face mask, and he experimented with the first coach-to-quarterback radio system.

This contraption is one Paul Brown innovation that didn’t work. It was created in the 1950s by a former employee of the Brunswick bowling ball company who pitched his invention as a “ball warmer” that could keep footballs warm and dry during cold and rainy days. Paul Brown tried to use the device in a Cleveland Browns exhibition game played in the old Akron Rubber Bowl. The Browns placed a game ball that was to be used for a kickoff into the warmer. However, this unusual heater hardened the leather of the football, and the Browns’ place-kicker almost injured himself when he struck it. The kickoff of the “ball warmer” innovation had failed and became a relic of history.

Brett Favre’s Thigh Pads (only artifact to go on display, then sent back to a team for play and then returned for display)

What is so unusual about these thigh pads? Well, this is the only artifact or football equipment to go on display at the Pro Football Hall of Fame and then be sent back to the field of play. Brett Favre wore these old-looking pads for the Green Bay Packers when he surpassed Dan Marino as the all-time leader in passing yards on Dec. 15, 2007 against the St. Louis Rams. The Pro Football Hall of Fame collected Favre’s record-setting complete uniform and exhibited it in our Pro Football Today Room.

After the 2007 season, Favre announced he would retire but changed his mind as NFL training camp neared. Eventually the Packers traded Favre to the New York Jets, where he became their starting quarterback for the 2008 NFL season. During the middle of the 2008 season, the Pro Football Hall of Fame received a call from the New York Jets’ equipment manager asking if Favre could have his thigh pads back.

The equipment man expressed to the curator of the Pro Football Hall of Fame that Favre had used these pads throughout his career and his new thigh pads were uncomfortable. Favre promised he would return the pads after he was done using them. True to their word, the New York Jets and Favre returned the thigh pads after the 2008 NFL season. When he returned with the Minnesota Vikings a year later, he did not ask for the pads again. Apparently, Favre finally has become accustomed to the new style of thigh padding.

Cleveland Skeletons 1930s full-leather facemask helmet (looks like a hockey mask attached to a helmet)

Believe it or not, this is a football helmet. It was worn by Chuck Culotta of the Cleveland Skeletons, an early 1930s semi-pro football team. The Skeletons wore leather helmets and uniforms that featured a white, glow-in-the-dark skeletal design. The idea apparently was for the team to intimidate their opponents with their scary uniforms, but the outfit scared few, considering the team folded after a couple of years of existence.

The Skeletons were a short-lived team, but this helmet – with its full-leather mask – is a great example of an early attempt at facial protection. The full leather mask style of protection never caught on because most players felt it was too hot to wear. The design was most likely based on the 1910’s and 1920’s “intimidator” helmet that had a leather mask that only covered the forehead, eyes and nose. Some players wore the “intimidator” style of helmet if they wanted to hide their identity because they were a collegian or because they didn’t want to be associated with pro football. At the time, some saw professional football as a dishonorable sport.

William “Refrigerator” Perry’s size 23 Super Bowl XX Ring (largest SB ring ever made)

Everything about William “Refrigerator” Perry was larger than life, including this Super Bowl XX ring he won as a rookie on the famed 1985 Chicago Bears. The average male wears a size 10 ring; the average Super Bowl player wears a size 13 ring. William “Refrigerator” Perry’s size 23 ring is the biggest ever manufactured.

Perry became a fan favorite – a jovial giant defensive tackle who was 6-foot-2 and 335 pounds. His fame grew as the Bears experimented with Perry as fullback on offensive goal line formations during the ’85 season. He eventually got the chance to rush and receive the football in scoring situations. He totaled three touchdowns on offense in the regular season and score another rushing touchdown in Super Bowl XX. No one had seen a man of such immense size score an offensive touchdown in the Super Bowl before or since. He played nine seasons in the NFL (1985-1993 Chicago Bears, 1993-94 Philadelphia Eagles).

Larry Primeau’s Packelope Helmet (deer antlers attached to helmet)

Is this a helmet safety experiment gone wrong? No, this helmet was created by Green Bay Packers super fan Larry Primeau, who was known as the “Packelope.” Larry was a winner of a past Pro Football Hall of Fame fan contest and exhibit called the Visa Hall of Fans, and he donated his helmet for exhibition. Larry would visit the Hall regularly to see his helmet. His helmet was also exhibited by the Wisconsin Historical Society because they felt it represented the two great loves of men from Wisconsin: deer hunting and the Green Bay Packers.

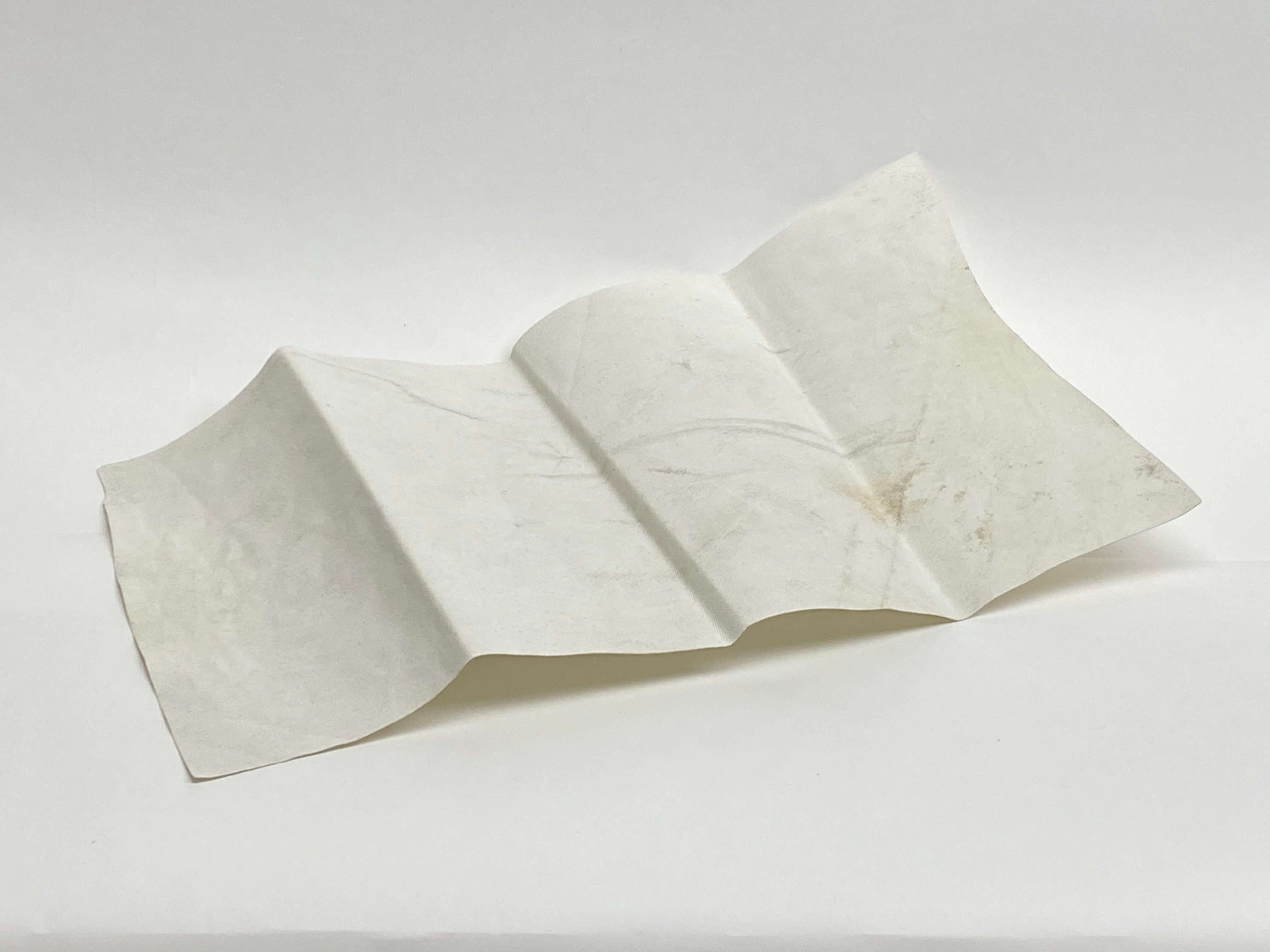

Pontiac Silverdome Roof fragment (Silverdome former home of the Detroit Lions)

This is not the playbook of a winless NFL team. This is a piece of the Pontiac Silverdome roof donated after the indoor stadium was repaired in 1985. The Silverdome hosted Super Bowl XVI and was home of the Detroit Lions from 1975-2001. Prior to making the Pontiac Silverdome their home, the Lions played outdoors at Tiger Stadium. Today the Lions play in another indoor stadium, Ford Field.

Prior to the Silverdome being built, the Lions had been seeking a stadium they could call their own for years. Tiger Stadium was also the home of Major League Baseball’s Detroit Tigers. The idea of an indoor stadium for the Lions stemmed from the Lions’ 1968 Thanksgiving game against the Philadelphia Eagles. A rainstorm during the game turned the field into a mud pit. By the end of the game, Eagles and Lions became indistinguishable. The Lions lost the game 12-0. The equipment manager reported 11 pairs of shoes lost to the mud. William Clay Ford, the owner of the Lions, was embarrassed that a national television audience had seen the game and immediately sought proposals for an indoor stadium, leading to the eventual construction of the Silverdome.

Nose Guard (circa 1900)

This might look like a medieval athletic supporter, but it was designed to protect a football player’s nose. This rubber nose guard, patented in 1892, was the first attempt at facial protection in football. It retailed for $2.50 and advertised as providing “absolute protection.” The strap on the nose guard was intended to be tied around a player’s head.

Years later, players attached them to earmuffs or early versions of a helmet called a head harness. The backside of the nose guard featured a protruding part that was to be bitten down by a player’s teeth to hold the guard in place. The nose guard was made of a hard rubber and often did more harm than good. Legend has it that some players used it as a weapon. By the 1910s, it fell out of favor with players and retailers.

Goal Post T-Joint from the 1945 NFL Championship Game (Sammy Baugh threw a pass off this goal post resulting in a safety and a 15-14 defeat)

This is not something left behind by your home plumber. This a T-joint to a goal post from the 1945 NFL Championship Game played between the Washington Redskins and the Cleveland Rams in Cleveland Stadium. In the 1940s, goals posts were white and were made either of metal pipe (such as this piece) or wood.

The goal posts in 1945 championship played a crucial role in the outcome of the game. In that era, unlike today, the goal posts were set on the goal line. In the first quarter of the game, Sammy Baugh went back to pass in his own end zone and accidentally threw the ball against his own goal post. At that time if a player threw a football from his own end zone and it hit the goal post and landed on the ground, the play would be ruled as a safety and two points would be awarded to the defense.

In the second quarter, the Rams scored their first touchdown on a 37-yard pass from Bob Waterfield to Jim Benton. Waterfield also served as the Rams’ kicker, and for good measure his extra point was partially blocked and hit the cross bar before tumbling over for a suspenseful but successful conversion. The safety turned out to be the deciding points in the game as the Rams defeated the Redskins 15-14 during a cold and wintry day in Cleveland. Furious about the outcome, Redskins owner and future Pro Football Hall of Famer George Preston Marshall had the rule changed at the next owner’s meeting. The goal posts were not moved to the end line of the end zone until 1974.

Tom Dempsey tape job (Dempsey kicked with his half foot)

The result of players wrapping medical tape around their own wrists and ankles is often referred to as a “tape job.” This artifact is a “tape job” from around Tom Dempsey’s kicking foot that was cut off and removed and donated to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1970. That same year Dempsey kicked a then-NFL record 63-yard field goal. A shoe that he wore that record season was also donated. Dempsey kicked for 11 seasons in the NFL (1969-1970 New Orleans Saints, 1971-74 Philadelphia Eagles, 1975-76 Los Angeles Rams, 1977 Houston Oilers, 1978-79 Buffalo Bills). He was born with no toes on his right foot and no hand on his right arm. His dominant leg was his right and special shoes were designed to compensate for the shape of his foot.

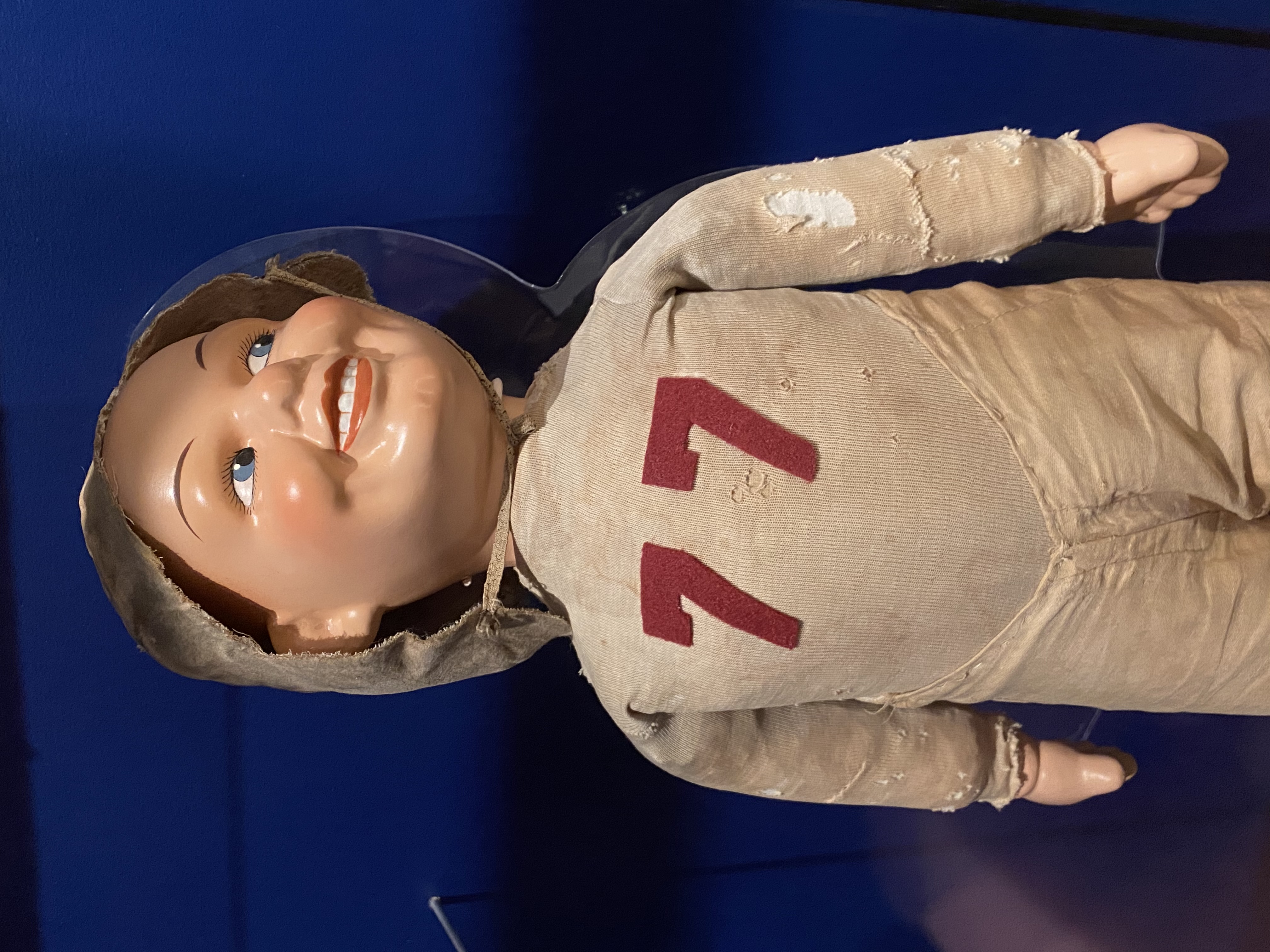

Harold “Red” Grange Doll (sold as a licensed merchandise in the 1920s)

This doll is not a Halloween decoration. It is a Harold “Red” Grange doll from the late 1920s. The doll was in very poor condition when it was donated to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1997. The Hall arranged for a “doll doctor” to restore it, and the doll is currently on display in our First Century of Pro Football Gallery. You might ask, “Why would the Hall go through the expense of restoring a doll, let alone collect one?” The doll is representative of Grange’s impact on professional football both on the field and off it.

Grange was the NFL’s first college football star. Known as the “Galloping Ghost,” Grange’s running style and big-play ability at running back drew huge crowds both at home at the University of Illinois and on the road. Fan attendance of over 75,000 were common in college football at the time, but NFL games drew a fraction of that amount. Grange planned on turning his college football success into a riches in the NFL. He signed with football’s first player agent, C.C. Pyle, and after his last game with the University of Illinois on Nov. 21, 1925, he joined the Chicago Bears for the remainder of their season.

In his first game with Bears, on Thanksgiving, Grange drew a crowd of 36,000 for an NFL record. Later that season, 70,000 fans poured into the Polo Grounds in Manhattan to see his Bears play the New York Giants. After the regular season, the Bears realized the financial dividends of Grange’s popularity and went on an exhibition barnstorming tour across the country, drawing huge crowds.

Pyle arranged for Grange to appear in movies and endorse numerous products, such as candy bars and malted milk. He also sold his likeness for souvenirs such as this doll. Today, NFL player endorsements and business deals are commonplace, but Grange was the league’s celebrity pioneer, paving the way for future stars to have success on and off the field.

Elevator Panel from Three Rivers Stadium (Art Rooney was famously in an Elevator when the Immaculate reception occurred)

What does an elevator panel have to do with football? When Three Rivers Stadium was demolished in 2001, Dan Rooney, the owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, instructed maintenance staff to save this elevator panel and have it donated to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Why? The panel was from the same elevator that Dan’s father and Pittsburgh Steelers founder, Art Rooney, rode in while the famed “Immaculate Reception” occurred in the Steelers’ 13-7 victory over the Oakland Raiders in the 1972 Divisional Playoffs.

How did Art Rooney miss the “Immaculate Reception?” With 26 seconds to play and trailing the Raiders 7-6, the Steelers faced a fourth-and-10 from their own 40-yard line. At that moment, the Steelers patriarch had seen enough. He decided to leave his owner’s box and take the elevator to the Steelers’ locker room to ensure he could console his team as the players came off the field.

Rooney also wanted to congratulate them for making the playoffs for the first time since 1947. As he rode the elevator, Bradshaw launched a pass toward John “Frenchy” Fuqua. As the ball came toward Fuqua, Oakland Raiders safety Jack Tatum hit Fuqua and the ball, sending both players to the right, but the ball was sent backward 9 yards to Franco Harris, who was trailing the play. Both Fuqua and Tatum fell to the ground. Harris caught the ball and scampered down a clear left sideline, untouched, for a touchdown.

When the elevator door opened for Rooney, a security guard ran up to him and said, “You won it!” Rooney asked him if he was kidding, and the security guard said, “No, listen to the crowd!” Rooney could hear roars from the crowd through the walls. However, there was confusion whether the play would stand. The Raiders said the play was illegal because, they claimed, Tatum never touched the ball but Fuqua did touch it. The Raiders said it was against the rules to have two offensive players touch the ball, one after the other, on a pass play.

Rooney went to the locker room to get clarification on what happened. He waited for what seemed to him an eternity. What is forgotten is that after the touchdown was declared legal, five seconds remained on the clock. The kickoff went into the end zone and the Raiders attempted one last pass before the game was over. Finally, Steelers punter Bobby Walden ran into the locker room jubilantly giving the Rooney the news the Steelers indeed had won. Rooney had missed the “Immaculate Reception” and the Steelers’ miracle victory while in the elevator. Luckily for everyone, Dan Rooney saved his father’s story for us to enjoy.

George Ratterman helmet receiver (this is a component of the 1956 Ratterman QB to Coach radio helmet)

This might look like something from your old Radio Shack store, but it is quite revolutionary. It is a component to the first coach-to-quarterback radio helmet that was implemented by Paul Brown of the Cleveland Browns in 1956. The idea of a coach-to-quarterback radio system was pitched to Brown by two Cleveland inventors, John Campbell and George Sarles. Brown had become famous for relaying his offensive plays to the quarterback via one of his offensive guards who substituted in and out of the huddle with new play calls.

Brown was always looking for innovative approaches to be a more efficient coach, and he instituted the system with the Browns breaking in a new starting quarterback in George Ratterman, who was replacing the retired Otto Graham. As the system was developed, he instructed everyone to secrecy. The helmet was first used in an exhibition game against the Detroit Lions.

As the game unfolded, the Lions’ coaching staff noticed Brown was not using his usual substitutions for play-calling. Shortly after halftime, one of the Lions’ assistants spotted the hidden transmitter that sat behind a wooden light post on the sideline. The Lions considered this cheating. In the second half of the game, Lions defenders ripped off Ratterman’s helmet at least twice and tried to punch and destroy the radio. After the game, news quickly spread throughout the league, and other teams scrambled to devise their own units, none of which proved as effective as the Sarles-Campbell invention.

Other teams took the approach to develop their own countermeasures to the radio system as many in the NFL considered its use unfair. In Week 3 of the NFL season, the Browns faced the New York Giants, and the Giants vowed to crack the radio system. During the course of the game, rumors began to circulate on the Browns’ sideline that the Giants were attempting to steal Ratterman’s radio signal. With the score tied 7-7, Brown decided not to use the helmet in the second half. The Browns went on to lose the game 21-9.

In newspaper articles that followed, the Giants’ general manager said the team stole the signal. Tom Landry, the Giants’ defensive coordinator, also said in his book that his team stole the signal and used a former Browns player to decipher the play calls. By the end of the week, NFL Commissioner Bert Bell banned the radio helmet. In all, the Browns used the helmet in four games. In 1994, almost 40 years later, the NFL brought back a radio system. Once again, Paul Brown was proven to be ahead of his time.

Edgerrin James Hair (he removed it after being tackled by the hair against the Browns in 2003)

Why is the Pro Football Hall of Fame preserving hair? This hair belonged to Edgerrin James, who cut it after a Cleveland Browns opponent tackled him by the hair in the 2003 NFL regular-season opener. Throughout his 10-year career (1999-2005 Indianapolis Colts, 2006-08 Arizona Cardinals, 2009 Seattle Seahawks), Edgerrin not only was known for his versality as a runner/receiver, but for his long dreadlocks as well. After suffering a hair tackle, James cut his hair, saved it and donated it to Hall after being elected to the Centennial Class of 2020.

Dreadlocks and long hair became popular among many NFL stars, among them Ricky Williams and Larry Fitzgerald, in the 2000s and 2010s, but it has become a tempting target for tacklers. A hot topic of debate has become whether tackling by the hair should be legal or not. Although the topic has been discussed by the NFL Rules Committee, it is still legal to tackle a player by the hair. Hair tackling videos are popular on YouTube, and the legality of it is still debated today. After James’ infamous hair tackle, he never let his hair totally flow out of his helmet again, but his famed dreadlocks always will be preserved at the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

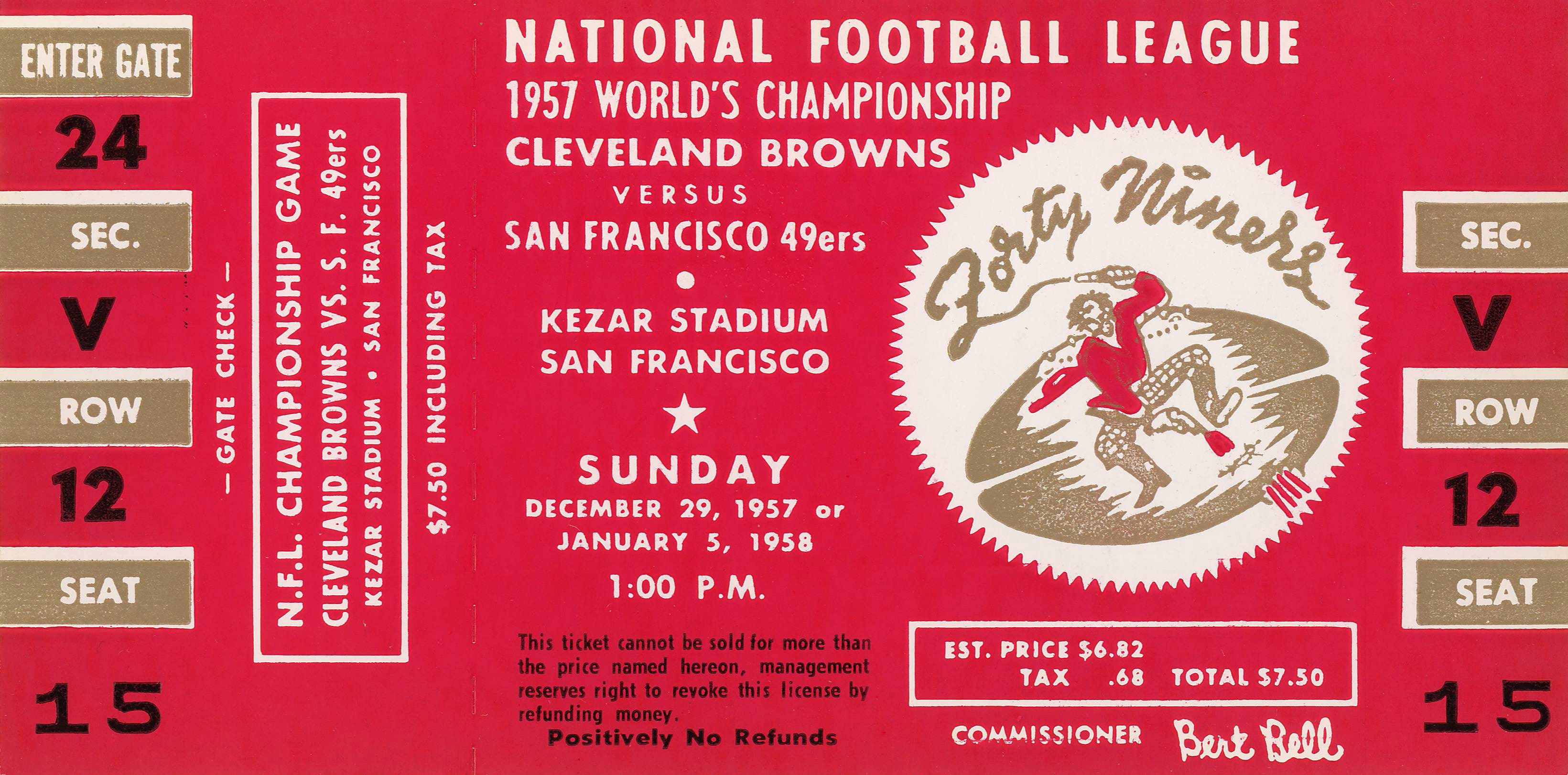

Ticket to the NFL Championship Game (1957) that never occurred (Leading the Lions the 49ers printed tickets to the Championship Game but they lost lead and game)

This is a ticket for a 1957 NFL Championship Game between the Cleveland Browns and the San Francisco 49ers in San Francisco’s Kezar, Stadium. The problem is that this game never occurred. The 1957 NFL Championship Game was played between the Cleveland Browns and the Detroit Lions in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium later to be named Tiger Stadium.

The Detroit Lions had a dubious beginning to their 1957 NFL Season. Their Head Coach Buddy Parker, who had led them to Championships in 1952 and 1953, quit in the offseason and took the Head Coach position with the Pittsburgh Steelers. New coach George Wilson instituted a rotating quarterback system with Tobin Rote and future Hall of Famer Bobby Layne. Wilson also used a revitalized, defense led by future Hall of Famer Jack Christiansen, Yale Lary and Joe Schmidt to battle the Baltimore Colts and the San Francisco 49ers for first place all season long

Wilson’s rotating quarterback system paid dividends at the end of the season when Bobby Layne broke his leg with two games to go. Rote led the Lions to victory against the Cleveland Browns and the Chicago Bears in the final two weeks of the season giving the Lions an identical 8-4 record with the San Francisco 49ers and forcing an extra playoff game to see who would represent the Western Conference in the NFL Championship game against the Cleveland Browns.

In the playoff game on December 22, 1957, the 49ers raced to a 24-7 halftime lead behind future Hall of Famer’s Y.A. Tittle’s three touchdowns. In the halftime locker room, the Lions could hear the 49ers laughing and celebrating their huge lead in the locker room. At that time in NFL history a 17-point lead was considered even more insurmountable than it is today. Even the 49ers ticketing staff considered the game won. In the third quarter of the game they announced that tickets for the Championship Game such as these ones were now on sale!

In the third quarter the 49ers built their lead to 27-7 after a 71-yard run by future Hall of Famer Hugh McElhenny set up a field goal. The 49ers got the ball back a second time in the third quarter and drove to the Lions 27-yard line, but Tittle fumbled late in the 3rd quarter. Still steaming from the halftime laughter, the Lions heard, the team miraculously in the next four minutes and 30 seconds erased the 49er’s 20-point lead.

After the fumble the Lions drove 73 yards in nine plays culminating in a one-yard touchdown run by fullback Tom “The Bomb” Tracy who had relieved an ailing future Hall of Famer John Henry Johnson. On the 49ers next possession, the Lions forced a punt and one play later Tracy took off for a 58-yard touchdown run. Now down only 27-21 late in the third quarter the Lions defense held again and, on the Lions, ensuing possession they scored the go ahead points on a two yard run by Gene Gedman 44 seconds into the 4th quarter. The 49ers once insurmountable lead had evaporated in a matter of minutes.

In the 4th quarter the Lions defense took over forcing four turnovers including three interceptions by Tittle. At the final gun the Lions won 31-27. The 20-point comeback still ranks as the third greatest comeback in NFL postseason history. The following week the Lions destroyed the Cleveland Browns 59-14 holding future Hall of Famer Jim Brown to 69 yards rushing to win the NFL Championship.

Elmer Angsman’s Contact Lenses

Contact Lenses have come a long way since the hard-plastic type worn by Pro Bowl running back Elmer Angsman of the Chicago Cardinals (1946-1952). The concept of contact lenses is credited to Leonardo DaVinci who theorized that vision could be corrected by submerging one’s head into a glass bowl. He went on to create a glass lens with a large funnel on one side for water to be poured into it. The design was impractical and never adopted widely.

It was not until the late 19th century that a circular lens was developed that could be applied directly to the eye with an applicator. These were like Angsman’s lenses except that they were made of glass which is quite dangerous for use on a football field. In the 1930s developments in plastics technology allowed manufacturers to develop lenses made from plastic. Many individuals complained they could not close their eye lids fully with these hard-plastic lenses. For years manufacturers and inventors worked to develop a soft plastic lens. Finally, in 1971 soft lenses were approved in the United States.

Using these contact lenses and applicator, Angsman went on to a legendary career in the NFL. He was part of the original “Million Dollar” backfield consisting of Hall of Famer Charley Trippi, Paul Christman and NFL scoring champion Pat Harder. The group earned the “Million Dollar” backfield nickname when Trippi signed with the team in 1947 for $100,000 which was the largest ever sum in the NFL up to that time. With the addition of Trippi, the Cardinals won the NFL Western Division and faced the Philadelphia Eagles in the 1947 NFL Championship Game. Angsman’s 70-yard touchdown run in the game helped the Cardinals defeated the Eagles 28-21

Pro Football Hall of Fame reopens doors to public

The Pro Football Hall of Fame reopened its doors to the public after nearly three months.

Huddle Up America Listen

It is a history-changing moment in time for America. There are many voices, opinions and reactions that churn every day with a new take, a new twist, a new narrative.