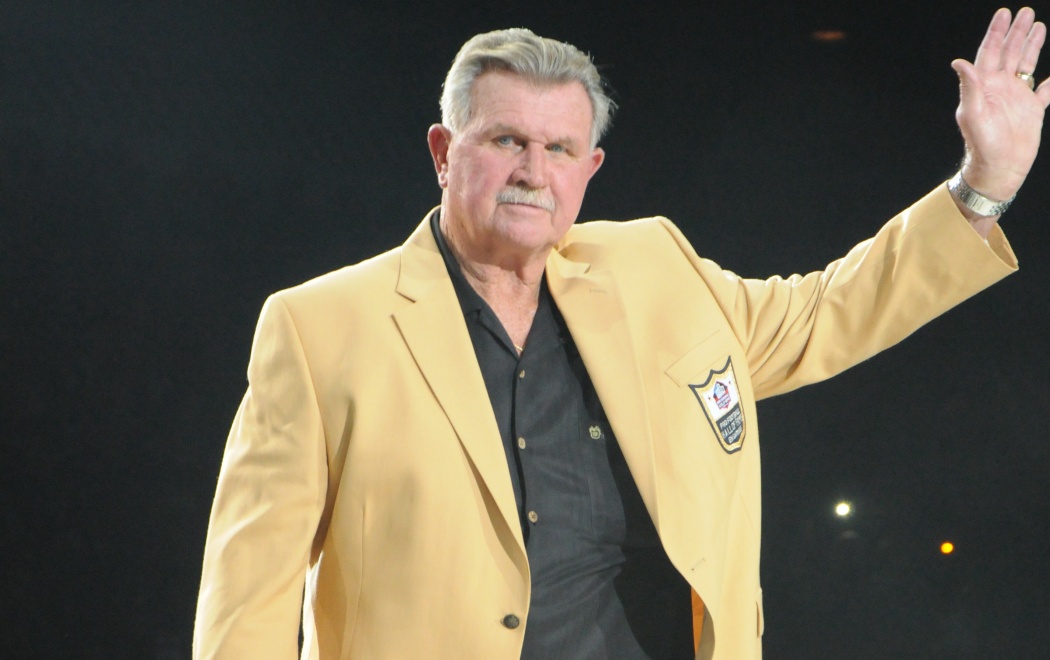

Gold Jacket Spotlight: 'Iron Mike' Ditka

Imagine a parallel universe in which a multisport standout at Aliquippa High School uses his football talent to attend the University of Pittsburgh. Never expecting to become a pro athlete, he completes the courses and training necessary to fulfill the vocational goal of his youth.

A few years later, with his bachelor’s and advanced degrees in hand, he begins his career.

Dr. Mike Ditka, DDS.

Now, if the thought of Mike Ditka with a dental drill in hand evokes teeth-clenching terror, his post-procedure news conferences might provide some relief.

“I tell them how to brush; they don’t want to brush my way. I tell them to floss; they don’t floss at all. And they ask for Novocaine when I fill a cavity. Novocaine!! I’ll tell ya, gang, these patients need to get tougher!”

In real life, “Iron Mike” did intend to become a dentist, but a couple of years into his All-American career at Pitt, he changed course. The result – a lifetime devoted to the game he loves – seems much more fitting for a man whose approach as a player, coach and commentator reflected a lot more black-and-blue collar than white.

His illustrious NFL career is revisited this week in the Gold Jacket Spotlight.

Mike burst onto the scene as the fifth overall pick of the 1961 NFL Draft. That he was taken that high wasn’t the surprise; that the Bears intended to use him at tight end, not at linebacker, raised a few eyebrows, however.

“No one knew what the heck it was,” Mike told NFL Films about his role as a pass-catching tight end who could provide a deep threat for the offense. “Tight ends when I came into the game were kind of an extension of the offensive tackle. They blocked most of the time.”

Not anymore.

On his way to earning Rookie of the Year honors, Mike caught 56 passes for 1,076 yards – the first time in NFL history a tight end eclipsed 1,000 yards – and 12 touchdowns. He received the first of his five consecutive Pro Bowl berths.

Mike would lead all NFL tight ends in receptions each year from 1961 to 1964, averaging 62 catches for 918 yards over those four seasons. Make no mistake, though, he was equally effective as a blocker, and his skills – and demeanor – matched exactly what Hall of Fame coach George Halas envisioned in Chicago.

“The Bears stood for something. It was a toughness,” Mike said. “Take your lunch bucket to work, work eight hours and come home.”

In 1963, the Bears lost only once and eeked out a 14-10 victory over the New York Giants in the NFL Championship Game. Mike caught three passes – the Bears completed only 10 on that frigid day – for 38 yards as Chicago ended a 17-year drought without an NFL title.

The city would wait even longer for its next championship, and Mike would figure prominently. After nine seasons as an assistant coach in Dallas, he returned to Chicago as the 43-year-old head coach of the Bears in 1982.

He promised the players that if they followed his regimen, then they would become world champions. A few rough patches early on created some doubt, but it all came together in Year 4.

The 1985 Bears rolled to an 18-1 overall record. Their defense, which allowed 10 points or fewer in 14 games, remains the measuring stick by which all others have been compared for nearly four decades.

With the 46-10 victory over the New England Patriots, Mike became the first person to win an NFL title as a player, assistant coach and head coach. (Only Class of 2021 enshrinee Tom Flores shares that distinction.)

Never one to mince words, Mike has filled plenty of airtime with memorable, sometimes controversial, one-liners delivered with blunt force. In his own way, he became an “oral surgeon” after all.

Brad Paisley and Lynyrd Skynyrd to Co-Headline 2021 Concert for Legends Presented by Ford

Concert caps annual HOF Enshrinement Week Powered by Johnson Controls

Pro Football Hall of Fame Enshrines Nine New Members

The Pro Football Hall of Fame added nine men to its list of legends Wednesday night.