Catch of a lifetime: Legendary 'Immaculate Reception' lives on 50 years later

‘Immaculate Reception’ set Steelers on course for Super Bowl binge

By Gerry Dulac

Special to the Pro Football Hall of Fame

One play. That’s all it took. One incredible, disputable, physics-examining moment that changed the course of a franchise, exhilarated a city and would come to be known by NFL Films as the greatest play in league history.

The “Immaculate Reception.”

December 23, 1972. Fifty years ago.

A moniker as great as the play itself.

It has spawned five decades of countless replays, narratives and barroom debates. Did it or didn’t it? Did the ball hit off the Steelers’ John “Frenchy” Fuqua or was it propelled backward by Raiders safety Jack Tatum? Only two types of people think they know for certain: those who root for the Pittsburgh Steelers and those who live and die with the Oakland Raiders.

For all its suddenness and drama, the Immaculate Reception proved to be more than simply a glorious moment in what was the first playoff victory in the 40-year history of the Steelers. The franchise that had been known for decades as the “Lovable Losers” — they had posted only seven winning records since their charitable and endeared owner, ART ROONEY SR., founded the franchise in 1933 — went on to become one of the most dominant in NFL history, winning four Super Bowls in a six-year period, beginning in 1974.

Ten players from those teams, plus head coach CHUCK NOLL, are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, including the two main principals of the Immaculate Reception: quarterback TERRY BRADSHAW and running back FRANCO HARRIS, a rookie from Penn State who was the leader of a growing fan club called Franco’s Italian Army.

Ten players from those teams, plus head coach CHUCK NOLL, are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, including the two main principals of the Immaculate Reception: quarterback TERRY BRADSHAW and running back FRANCO HARRIS, a rookie from Penn State who was the leader of a growing fan club called Franco’s Italian Army.“What makes it special is this is the first playoff victory for the Steelers ever, the first touchdown in Steelers playoff history, the first touchdown pass for Terry Bradshaw in Steelers playoff history and the first touchdown for myself in Steelers playoff history,” Harris said. “That play carried a lot of weight in so many different ways about being the first of so many things. The most important thing is, we found a way to win. That stayed with us for the rest of the decade.”

In a strange way, the magnitude of the defeat seemed to haunt the Raiders. After losing three consecutive AFL/AFC championship games in the years preceding what happened against the Steelers, they would go on to lose three more conference title games in a row, beginning in 1973. Finally, in 1976, the Raiders shook the frustration and won Super Bowl XI. Perhaps fittingly, they beat the Steelers in the AFC Championship Game in Oakland.

That was the start of the Raiders’ own dominating run. They soon added two more Super Bowl titles (XV and XVIII), meaning the Steelers and AL DAVIS' Pride and Poise boys combined to capture seven Vince Lombardi Trophies in a 10-year span.

Sadly, the person who most deserved to embrace the Immaculate Reception is the one who missed the play. Thinking the outcome was decided, Rooney already had left the press box to head to the locker room to console and shake hands with his players. “The Chief” was on the elevator at Three Rivers Stadium when the play occurred and he heard the roar. He was told what happened when he got off.

“We were winning and then, all of a sudden, with a minute or so to go, we’re losing,” Harris said. “And, once again, Mr. Rooney gets on an elevator to go down to the locker room to console us because, through his history, the Steelers had always found a way to lose. Here it is again — we’re winning and right at the end we’re losing.”

Only this time it was different.

“When he got off the elevator,” Harris said, “we had found a way to win.”

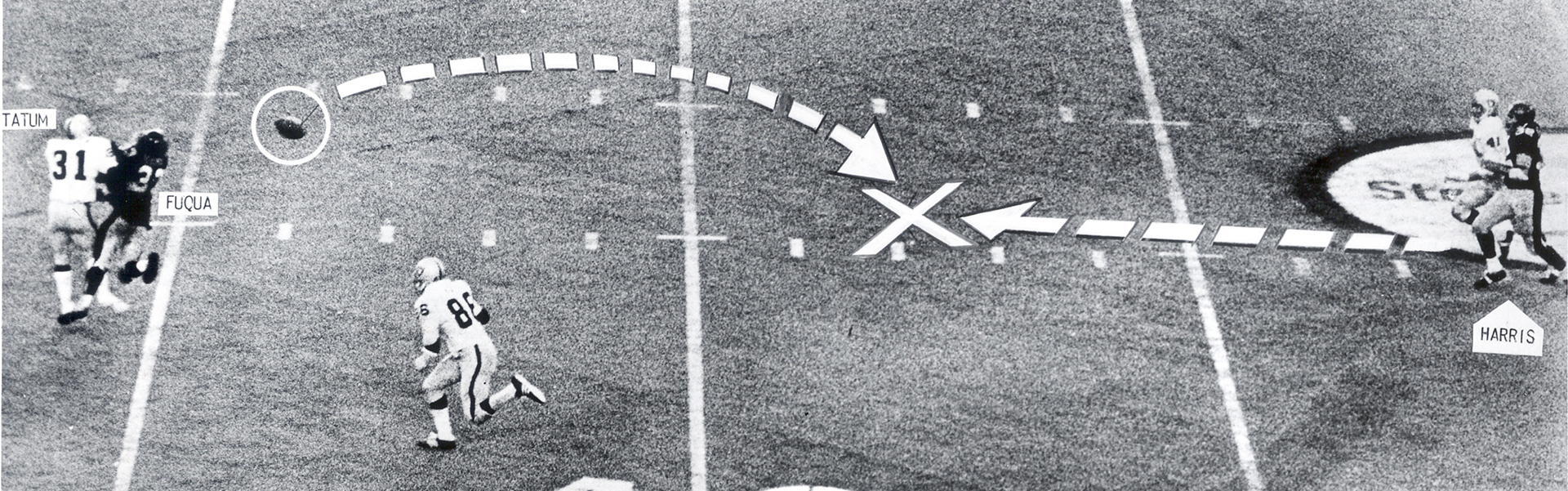

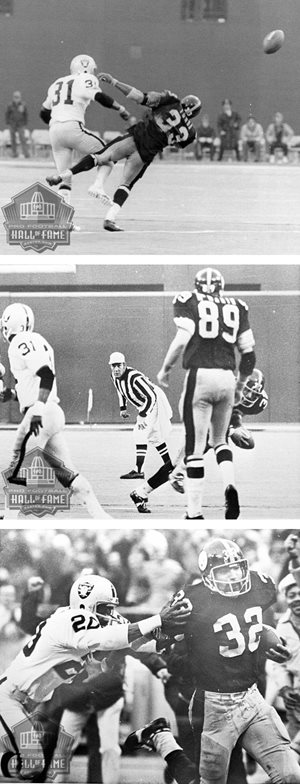

For more than 58 minutes, the game’s only points came on a pair of Roy Gerela field goals that gave the Steelers a 6-0 lead. But the Raiders went ahead on quarterback KEN STABLER'S 30-yard run and GEORGE BLANDA'S PAT, and now Pittsburgh faced a dire situation: fourth-and-10 at its own 40-yard line with 22 seconds remaining and no timeouts left. Coach Chuck Noll called for 66 Circle Option, but the play broke down quickly because of the Raiders’ pass rush. Bradshaw scrambled and threw across the middle to his fullback Fuqua, who immediately was met by the hard-charging Tatum.

What happened next is where the controversy starts.

“The ball definitely hit Frenchy,” said former Raiders linebacker Phil Villapiano, whose assignment on the play was to cover Harris out of the backfield. “I saw it. Because Tatum hit him so hard in the back, his shoulder went flying forward and the ball came — Bam! — like that. It took a massive blow to make that ball ricochet.”

Harris caught the deflected pass just before it hit the ground at the Raiders’ 42 and raced down the left sideline, avoiding one last tackle from cornerback Jimmy Warren at the 10 and tight-roping into the end zone. The shoestring catch is immortalized with a statue in the Pittsburgh International Airport, for all heading to baggage claim to see.

What made the play even more frustrating for the Raiders is they brought in six defensive backs — a package they had never used before — to prevent the very thing that happened. Tatum was positioned between the hash marks almost as a spy, looking for anything to come over the middle.

And it did.

“It was heartbreaking to us because I remember being in the huddle, and the last thing we said was, ‘It’s fourth down. Even if the receiver catches it, make sure we make the tackle,’ ” said former Raiders cornerback George Atkinson.

According to NFL rules in 1972, a receiver could not legally catch a pass that had been touched, batted or deflected by another offensive player. Officials were not certain if Bradshaw’s pass had hit Fuqua or Tatum to cause the ball to propel backward. So they huddled.

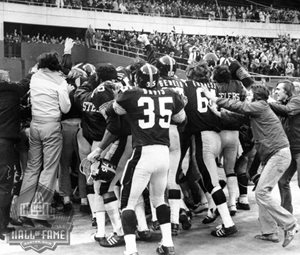

In the meantime, Steelers fans had begun pouring onto the field to celebrate, even though five seconds remained. The mayhem was unlike anything the NFL had seen. And yet, no official signal of touchdown had been made.

After a conference with his officials, crew chief Fred Swearingen was ushered by Steelers official Jim “Buff” Boston over to a phone in the baseball dugout that connected to the press box. Instant replay wasn’t an option then, so Swearingen wanted to talk to ART McNALLY, the NFL’s director of officiating (and 2022 Pro Football Hall of Fame enshrinee), who was stationed upstairs.

Joe Gordon, the Steelers’ longtime director of media relations, answered the phone.

“Buff says, ‘Swearingen wants to talk to McNally,’ ” Gordon said. “Soon as I picked up the phone, Art was by my side. I said, ‘Here, Art, the ref wants to talk to you.’

“I heard the whole conversation on Art’s end. He said, ‘What do you see? Well, call it.’ And that was the extent of it. I’d say the conversation was no more than 15-20 seconds. Soon as he said that, Swearingen went out on the field and made the call.”

That’s not the way the Raiders like to tell the story.

Atkinson said he wandered over to the dugout to hear what they were talking about, thinking the play would be blown dead.

“Instead, they were concerned about security. I heard it with my own ears,” Atkinson

said. “They were concerned how much security was there if they made the wrong call. Other than that, why would they have to call upstairs? For what? There was no instant replay. They were calling security there.

said. “They were concerned how much security was there if they made the wrong call. Other than that, why would they have to call upstairs? For what? There was no instant replay. They were calling security there.“Next thing we knew, they had their arms up in the air (signaling a touchdown).”

The ending was a final slap of what began as a bizarre and ignominious trip for the Raiders. The night before the game, tight end Bob Moore was clubbed over the head by a Pittsburgh police officer as he and a teammate tried to enter their team hotel through a crowd of Steelers fans. “Raiders’ Moore Gets Early Playoff Lumps” ran one headline of the account.

Twenty-four hours later, the Raiders and their fans were dealt another blow, one not softened by being part of arguably the greatest, most improbable and “immaculate” play ever.

Gerry Dulac has covered the Steelers for more than 30 years for the Pittsburgh Press and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. In addition, he has been a host on the Steelers Radio Network for 25 years. This article originally appeared in the 2022 Hall of Fame Yearbook.

Previous Article

Cliff Branch's family to receive Pro Football Hall of Fame Ring of Excellence after policy change

Decision to present iconic symbol of membership in sport’s most exclusive club follows ‘passionate discussions’ with families.

Next Article

'The Mission:' Pro Football Hall of Fame Class of 2006's Warren Moon

To help look ahead to Week 13 of the NFL schedule, joining The Mission this week is Houston Oilers Legend Warren Moon, a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s Class of 2006.